A narrative review, qualitative analysis and development of a conceptual model of workplace stress factors among non-clinical healthcare staff

Introduction

Workplace stress refers to the harmful physical and emotional responses that occur when job demands exceed the worker’s abilities and resources to cope effectively (1). Workload burden has been identified as a top contributor to workplace stress for many (2), which results from exposure to issues such as poor communication, lack of appreciation, and lack of autonomy, all of which can contribute to an undue sense of pressure for people working in that environment (3,4).

Workplace stress is incredibly common, with 83% of workers in the U.S. reporting experiencing workplace stress in 2022. Chronic exposure to this type of stress can lead to burnout—a state of physical, emotional, and mental exhaustion characterized by feelings of cynicism, detachment from work, and reduced professional efficacy (5-7). Burnout has significant personal and professional implications, affecting not only individual well-being but also job performance, patient safety, and overall healthcare system efficiency.

There is extensive research on workplace stress within healthcare settings, typically focusing on its impact on frontline clinical healthcare workers like nurses and physicians. There has been less attention focused on workplace stress for non-clinical members of the healthcare workforce, including administrative, finance, janitorial, clerical, and research roles. Staffing shortages, emotional intelligence deficits, workplace violence, and shift work contribute significantly to workplace stress for everyone working in the healthcare industry; however, non-clinical support staff may face distinct challenges from their patient-facing colleagues (8-10). In addition to shared stressors, non-clinical support staff also contend with additional pressures emanating from their interactions with clinical staff members which may be a unique source of workplace stress (1).

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has had a profound and lasting impact on healthcare systems worldwide, significantly altering the work environment and stressors faced by all healthcare workers, including non-clinical support staff (4,11). While the pandemic introduced new challenges, it also exacerbated many pre-existing issues in healthcare settings (12,13). For non-clinical staff, this meant adapting to rapidly changing protocols, increased workloads, and new safety concerns, often while working remotely or in altered workplace configurations (14,15). The pandemic’s effects have been so substantial that they have reshaped the landscape of workplace stress in healthcare, creating what many consider a “new normal” in terms of job demands and organizational dynamics (16). As such, understanding the impact of COVID-19 on workplace stress is crucial for comprehending the current and future challenges faced by non-clinical healthcare staff.

Several studies have explored the impact of workplace stress on administrative, finance, and research support staff within healthcare settings (4,11-16). These studies shed light on the challenging environments faced by these professionals. However, the existing literature lacks a comprehensive synthesis and analysis of how workplace stress specifically impacts well-being, job satisfaction, burnout, and other manifestations among non-clinical support staff in healthcare settings. Moreover, despite the growing recognition of workplace stress among healthcare workers in general, there is limited synthesis of evidence on effective interventions specifically tailored for non-clinical support staff. Understanding the unique stressors faced by this group is crucial for developing targeted strategies to enhance their well-being and job satisfaction.

This gap in the literature underscores the need for a comprehensive review that not only consolidates findings on workplace stress impacts but also evaluates the efficacy of current intervention strategies for this often-overlooked workforce segment.

Objectives

This narrative review focuses on healthcare support staff, defined as non-clinical professionals encompassing administrative, finance, research, janitorial, information technology (IT), and other support roles within the healthcare sector (17,18).

Our aim is to consolidate findings from prior studies and provide a holistic understanding of the unique challenges and effects of workplace stress on this often-overlooked workforce segment within healthcare organizations. Specifically, the key objectives are: (I) to identify the predominant factors contributing to workplace stress among support staff; (II) to assess how workplace stress influences support staff’s well-being, job satisfaction, and manifests in outcomes such as burnout, depression, anxiety, and exhaustion; (III) to determine if discernible variations exist in workplace stress experiences among different subgroups of support staff; and (IV) to develop a conceptual model that synthesizes the findings and illustrates the relationships between workplace stressors, job demands, resources, and their impacts on staff and organizational outcomes.

By integrating existing evidence, we aim to develop a more nuanced perspective on the factors contributing to stress, burnout, and diminished well-being for non-clinical support staff. This comprehensive analysis can inform the development of targeted interventions and strategies to enhance non-clinical healthcare support staff’s professional satisfaction, mental health, and overall well-being, ultimately improving retention and productivity within healthcare systems (19). It should be noted that the opinions expressed in this manuscript are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government. We used the Narrative Review reporting checklist (available at https://jhmhp.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jhmhp-24-88/rc) and the guidelines for writing narrative literature reviews by Green et al. [2006] as a guide for presenting this article (20).

Methods

Eligibility criteria

This narrative review includes peer-reviewed original research articles focusing on workplace stress among healthcare support staff, defined as non-clinical professionals in administrative, finance, research, janitorial, IT, and other support roles within the healthcare sector. We chose to include only peer-reviewed articles to ensure that the studies reviewed have undergone rigorous evaluation by experts in the field, thus maintaining a high standard of quality and reliability. The literature reviewed encompasses studies conducted in both academic and community healthcare settings. We considered studies providing data on factors contributing to workplace stress, as well as its impact on well-being, job satisfaction, and associated manifestations like burnout, depression, anxiety, and exhaustion among support staff. The inclusion criteria specified articles published from database inception until February 2024. The inclusion of articles was restricted to those written in English. To address the potentially limited availability of articles specifically on workplace stress among administrative, finance, and research support staff, we broadened the inclusion criteria to encompass articles presenting relevant data on workplace stress for non-clinical staff in healthcare settings. By expanding the scope of our review, we aimed to provide a comprehensive overview of the current knowledge on workplace stress experienced by healthcare support staff, while maintaining the focus on high-quality, peer-reviewed research.

Search strategy

We consulted with a research librarian to refine our search strategy and database selection. Based on this consultation, databases searched for relevant literature included PubMed, JSTOR, ProQuest, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. PubMed was chosen for its comprehensive coverage of biomedical literature, while JSTOR provides access to a wide range of academic journals spanning various disciplines, including healthcare and social sciences. ProQuest was selected for its extensive collection of peer-reviewed scholarly articles across multiple disciplines, enhancing the breadth of our search. Web of Science, known for its multidisciplinary coverage and citation indexing, was chosen to ensure a comprehensive retrieval of relevant articles.

We used Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and keywords ((‘non-clinical staff’) AND (‘Healthcare’ AND ‘Workplace stress’ OR ‘Burnout’ OR ‘Job stress’ OR ‘Burden’)) related to workplace stress, healthcare support staff, and relevant outcomes. The complete search strategy, including all search terms and combinations used, can be found in Table S1. The selection process included: (I) an initial screening of titles and abstracts; and (II) a full-text review of potentially relevant articles. The complete search summary strategy can be found in Table 1.

Table 1

| Items | Specification |

|---|---|

| Date of search | February 5, 2024 |

| Databases and other sources searched | PubMed, JSTOR, ProQuest, Web of Science, and Google Scholar |

| Search terms used | “Non-clinical staff” AND (“Healthcare” AND “Workplace stress” OR “Burnout” OR “Job stress” OR “Burden”) |

| Timeframe | Database inception to February 2024 |

| Inclusion and exclusion criteria | Inclusion criteria: peer-reviewed original research articles, articles focused on workplace stress among non-clinical healthcare support staff, and articles published in English |

| Exclusion criteria: articles not focusing on non-clinical healthcare staff, and non-English articles | |

| Selection process | Several authors (M.B., J.V., and J.A.) collaborated to develop the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Titles, abstracts, and full texts underwent screening to identify relevant articles. Two authors (M.B. and J.V.) independently reviewed and coded the full texts of included studies. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion and consensus among the full author team |

Data collection & management

Several of the authors (M.B., J.V., and J.A.) collaborated to develop the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Titles, abstracts, and full texts were screened to identify relevant articles.

Qualitative data analysis

Two authors (M.B. and J.V.) independently conducted a directed qualitative content analysis on the full texts of the 11 included studies, followed by a matrix analysis (21-23). This comprehensive approach allowed us to capture relevant information from all sections of the papers, including introductions, methods, results, and discussions. The coding process involved several stages. First, authors read through each paper to gain an overall understanding of the content. Then, relevant text segments were identified and assigned codes based on predefined themes, while allowing for emergent themes. Regular meetings were held between coders to discuss and resolve any discrepancies in coding. For theme development, we used matrix analysis to organize and synthesize the coded data. We created a matrix with studies as rows and emerging themes as columns, then populated it with relevant coded data from each study. By analyzing this matrix, we identified patterns, similarities, and differences across studies, which allowed us to refine and consolidate themes. Exemplary quotes were selected based on their representativeness of the themes and their ability to illustrate key points succinctly. Our selection criteria included relevance to the identified theme, clarity in expressing the concept, and representation of diverse perspectives across different studies and contexts.

Study selection process

The study selection process involved systematic screening of identified articles based on the eligibility criteria outlined above. The initial identification of potentially relevant articles based on titles and abstracts was conducted independently by two researchers (M.B. and J.V.), with subsequent screening and full-text review involving multiple team members as described above. We provided a descriptive summary of the article selection process, detailing the number of articles identified, screened, eligible, and included in this narrative review (Table 2). In the event of disagreements between reviewers during the selection process, resolution was sought through discussion and consensus.

Table 2

| Study | Country | N1 | N [%]2 | Design | Type of non-clinical staff | Main topics of study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adamis et al. [2023], (24) | Ireland | 396 | 99 [25] | Cross-sectional survey | Administrative, management, and support staff | Burnout, commitment, and effort-reward balance |

| Rotenstein et al. [2023], (25) | United States | 43,026 | 11,114 [26] | Cross-sectional survey | Administrative, clerical, support, janitorial, and food service staff | Burnout, intent to leave, and work overload |

| Ibrahim et al. [2022], (26) | Egypt | 3,502 | 3,502 [100] | Cross-sectional survey | Administrative, technical, engineering, information technology, and finance staff | Depression, anxiety, and perceived job stress |

| Pala et al. [2022], (27) | United States | 1,171 | 299 [26] | Cross-sectional survey | Administrative, clerical, support, janitorial, and food service staff | Depression, anxiety, occupational burnout, and financial strain |

| Jones et al. [2022], (28) | United Kingdom | 35 | 19 [54] | Convenience and purposive sampling | Administrative, clerical, and support staff | COVID-19 disease, interpersonal relationships, individual considerations, change, and working environment and support |

| Brady et al. [2023], (29) | Ireland | 229 | 54 [24] | Longitudinal survey | Administrative, clerical, and support staff | Post-traumatic stress symptoms, well-being and mood, suicidal ideation, moral injury, coping styles, perception of COVID-19 outbreak, altruistic acceptance of risk |

| Edwards et al. [2018], (30) | United States | 10,012 | 2,898 [29] | Cross-sectional survey | Administrative, clerical, and support staff | Burnout |

| Norman & Basu [2018], (31) | United Kingdom | 34 | 34 [100] | Longitudinal intervention study | Clerical staff | Demand, control, and support |

| Donovan et al. [2018], (32) | Australia | 23 | 23 [100] | Qualitative interviews | Administrative, clerical, and support staff | Exposure to occupational violence, impact of exposure to violence, work-related stress strategies |

| Grant et al. [2024], (33) | Canada | 19 (articles) | –3 | Narrative review | Various non-clinical staff in primary care teams | Workload and staffing issues; role clarity, communication, and team dynamics; work environment, resources, and supports; individual factors like beliefs, flexibility |

| Han et al. [2022], (12) | South Korea | 337 | 337 [100] | Cross-sectional survey | Administrative staff in general hospitals | Emotional intelligence, job stress, burnout |

1, overall N for each study; 2, non-clinical staff N [%] for each study; 3, this article was a narrative review, so there was not a summary total of non-clinical staff. COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

Conceptual model development

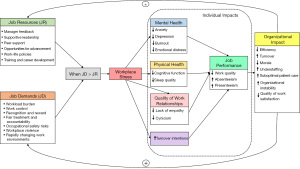

The development of our conceptual model was an iterative process that synthesized key themes and relationships identified through our literature review, following established guidelines for conceptual model development in healthcare research (34,35). We integrated the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) theory as a foundational framework, adapting it to the specific context of non-clinical healthcare staff based on our findings (36). As we analyzed the included studies, we noted recurring themes related to job demands, job resources, and outcomes, employing thematic analysis techniques (37). These factors were categorized according to the JD-R theory, distinguishing between job demands and job resources. We then mapped the various individual and organizational outcomes reported in the literature and identified relationships between factors based on the evidence from our reviewed studies, a process aligned with the principles of qualitative synthesis (38). The model underwent several rounds of revision as we collaboratively discussed and integrated new insights from our ongoing analysis, reflecting the iterative nature of conceptual model development (39). Finally, we created a visual diagram to clearly illustrate the relationships between all components of the model, adhering to best practices in visual representation of conceptual frameworks (40).

Results

Study selection and characteristics

The systematic search yielded 147 articles, of which 11 met the eligibility criteria for inclusion in this narrative review (Figure 1). The included studies were conducted in seven countries: the United States (n=3), Ireland (n=2), United Kingdom (n=2), Australia (n=1), South Korea (n=1), Canada (n=1) and Egypt (n=1). The study designs comprised cross-sectional surveys (n=7), longitudinal surveys (n=1), qualitative interviews (n=1), and a narrative review (n=1). The non-clinical healthcare staff investigated in these studies included administrative, finance, and other staff (Table 2).

Our analysis identified five main themes: (I) predominant factors contributing to workplace stress; (II) impact on well-being and job satisfaction; (III) variations across support staff subgroups; (IV) manifestations of stress (including burnout, depression, anxiety, and emotional exhaustion); and (V) interventions to mitigate stress and enhance well-being. These themes provide a comprehensive framework for understanding the complexities of workplace stress among non-clinical healthcare staff.

Factors contributing to workplace stress

Table 3 provides a comprehensive overview of the predominant factors contributing to workplace stress among non-clinical healthcare staff, as identified across the reviewed studies. The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly exacerbated existing challenges and introduced new stressors for non-clinical healthcare staff. Our review found that the pandemic exposed staff to additional stressors such as drastically increased workload, rapidly changing work environments, and heightened occupational health and safety concerns. These pandemic-related factors, combined with pre-existing issues, have underscored the essential role of non-clinical staff in maintaining healthcare system resilience and adaptability during crises.

Table 3

| Study | Main themes | Sub-themes |

|---|---|---|

| Rotenstein et al., 2023, (25) | Predominant factors contributing to workplace stress | Increased workloads and staffing Expanded job roles and responsibilities Time constraints and backlogs Lack of clearly defined responsibilities Loss of autonomy and control Poor leadership and inadequate support Perceived unfair treatment and breakdowns in trust |

| Jones et al., 2022, (28) | ||

| Brady et al., 2023, (29) | ||

| Norman et al., 2018, (31) | ||

| Donovan et al., 2018, (32) | ||

| Han et al., 2022, (12) | ||

| Pala et al., 2022, (27) | Impact on well-being and job satisfaction | High prevalence of burnout Increased risk of depression and anxiety Financial strain as a key driver Limited autonomy and unsupportive supervision Blurred boundaries between personal and professional lives High intention to leave jobs Psychological and physiological health consequences |

| Brady et al., 2023, (29) | ||

| Jones et al., 2022, (28) | ||

| Edwards et al., 2018, (30) | ||

| Rotenstein et al., 2023, (25) | ||

| Brady et al., 2023, (29) | Variations across support staff subgroups | Higher burnout in urban vs. semi-rural healthcare facilities Potential differences in financial strain across roles (e.g., admin vs. IT) Lack of comprehensive examination of variations across specific non-clinical roles |

| Ibrahim et al., 2022, (26) | ||

| Han et al. 2022, (12) | ||

| Pala et al., 2022, (27) | Manifestations: burnout, depression, anxiety, emotional exhaustion | High prevalence of severe/extremely severe depression and anxiety Links between workplace factors and higher depression/stress levels Financial hardship as a particularly strong predictor Physiological dysregulation and impacts on job |

| Ibrahim et al., 2022, (26) | ||

| Edwards et al., 2018, (30) | ||

| Adamis et al., 2023, (24) | ||

| Norman et al., 2018, (31) | Interventions to mitigate stress and enhance well-being | Limited evidence on rigorously tested interventions for non-clinical staff Potential benefits of co-designed interventions engaging leadership and frontline workers Need for comprehensive research on tailored intervention strategies Importance of addressing systemic issues (e.g., funding models, resource inadequacies) Cultivating resilience as an urgent strategic priority for healthcare organizations |

| Grant et al., 2024, (33) | ||

| Han et al., 2022, (12) |

IT, information technology.

The COVID-19 pandemic created substantial stressors for the non-clinical healthcare workforce. Increased workloads were attributed to staffing shortages, resource redirection, and the need for rapid process adaptations to meet evolving pandemic demands (24-26). As one participant in a qualitative study noted, “The workload has increased significantly, and we’re expected to do more with less” (27). Non-clinical staff experienced role expansions, taking on additional responsibilities beyond their usual scope including such things as changes in work environment, and personal safety concerns, which strained existing competencies and intensified time constraints as backlogs accumulated due to workflow interruptions (28,29).

Non-clinical staff have long experienced challenges related to control and autonomy, which were exacerbated during the pandemic. Studies spanning both pre-pandemic and pandemic periods revealed that staff often lack input into shifting priorities (25-28). One study participant expressed, “We have no say in the decisions that affect our work. It’s like we’re just expected to adapt and carry on” (30). Longstanding issues such as inadequate performance feedback, lack of supportive supervision, and limited opportunities for professional advancement were identified as factors impacting morale and job satisfaction (31). These challenges intensified during the pandemic. Perceived unfair treatment, inability to voice concerns, and breakdowns in trust and supportive relationships with colleagues and managers were reported both before and during the pandemic (27,28,31,32). As one participant stated in a pandemic-era study, “There’s a lack of trust and support from management. It feels like they don’t value our contributions” (32).

Impact of stress on well-being and job satisfaction

High levels of burnout, depression, anxiety, and emotional exhaustion have been consistently reported among non-clinical staff in healthcare settings. Burnout prevalence in recent studies ranged from 45% in a nationwide U.S. study, to 46% in an Irish study focused on mental health services (26,32). The South Korean study found that among administrative staff, 35.7% experienced high levels of emotional exhaustion, 20.5% reported high depersonalization, and 33.2% felt a low sense of personal accomplishment (12). The findings from Han et al. suggest that interventions aimed at enhancing emotional intelligence could be particularly beneficial for non-clinical healthcare staff (12). Their study indicated that emotional intelligence not only directly reduced burnout but also moderated the relationship between job stress and burnout (12). This highlights the potential value of emotional intelligence training as part of comprehensive stress management programs for administrative and other non-clinical staff in healthcare settings. These issues were further exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic. Perceiving substantial pandemic-related overload was associated with a nearly three-fold higher risk of burnout (24). A qualitative study from the United Kingdom specifically examined pandemic impacts, reporting increased stress, anxiety, and emotional exhaustion among non-clinical staff in a mental health trust due to challenges such as increased workload, changes in work environment, and personal safety concerns (26). One participant in this study shared, “I feel emotionally drained and anxious all the time. It’s taking a toll on my mental health” (26). The pandemic thus intensified pre-existing workplace stressors, leading to more acute manifestations of mental health issues among non-clinical staff. The various manifestations of workplace stress and their prevalence among non-clinical healthcare staff are summarized in Table 3, highlighting the significant impact on mental health and job satisfaction.

Limited autonomy, unsupportive supervision, and extreme time pressures from increased workloads were found to be associated with higher risks of depression, anxiety, burnout, and emotional exhaustion among non-clinical personnel (26,29). Remote work, while offering some productivity benefits, was reported to blur personal and professional life boundaries (26). As one participant described, “Working from home has made it difficult to switch off. It feels like I’m always on call” (26). In the U.S. study, burnout and dissatisfaction were associated with over 32% of non-clinical staff intending to leave their jobs within 2 years (24).

Variations in workplace stress across support staff subgroups

An Irish study found that non-clinical staff at urban healthcare facilities experienced significantly higher personal, work-related, and patient-related burnout compared to those in semi-rural settings (29). An Egyptian pre-pandemic study suggested some differences between administrative staff and engineering/IT professionals, with the former more likely to report financial strain and insufficient income (26). However, comprehensive examinations of variations in workplace stress manifestations across specific non-clinical roles were lacking in the reviewed studies.

Manifestations of workplace stress

The COVID-19 pandemic was associated with high levels of psychological distress among non-clinical staff across settings. In addition to the 45–46% burnout prevalence, one study using validated clinical scales found that 20.8% experienced severe or extremely severe depression, and 34.6% had severe or extremely severe anxiety (24,26,33). Emotional exhaustion frequently co-occurred, with 43% reporting simultaneous presence of depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms (30). As one participant expressed, “I feel like I’m barely keeping my head above water. The constant stress and exhaustion are overwhelming” (26).

The Egyptian study also identified several key determinants of emotional distress among non-clinical staff (26). Factors such as younger age, female gender, lower education levels, and certain job categories (particularly administrative and technical support roles) were associated with higher levels of emotional distress. Additionally, they found that staff with chronic diseases or a history of psychiatric disorders were more vulnerable to emotional distress in the workplace. Specific workplace factors, such as difficulty communicating concerns to leadership and managers, were directly associated with higher depression and stress levels among non-clinical staff (26). Financial hardship emerged as a significant factor, with increased financial strain being associated with positive screening for depression and anxiety when role was considered (24,25). One participant noted, “The financial stress is unbearable. It’s affecting my mental health and my ability to focus at work” (25).

Interventions to mitigate stress and enhance well-being

Rigorously tested workplace interventions targeting non-clinical healthcare staff are limited. A pre-pandemic study of emergency department clerical staff demonstrated the potential benefits of co-designed interventions engaging both leadership and frontline non-clinical workers (31). Improvements were observed in perceived work control, social support, and manager feedback, which are protective factors against burnout in high-stress environments. As one participant remarked, “The intervention helped me feel more supported and valued by my managers” (31).

While our search primarily focused on primary research articles, we included one recent narrative review, that met our inclusion criteria and provided valuable insights into systemic approaches to addressing workplace stress among non-clinical staff (33). This review complemented the primary studies by offering a broader perspective on organizational strategies (33). The findings of this review are consistent with a study by van Dijk et al., which was not included in the systematic search as it focused on a broader population beyond healthcare settings (41). van Dijk et al. found that burnout among non-clinical workers was associated with impaired cognitive functioning, particularly in the domains of updating, switching, and inhibition. They also reported that individuals with burnout experienced poorer sleep quality and reduced work performance (41). These findings complement our review by providing additional context on the far-reaching consequences of workplace stress and burnout on non-clinical staff.

Additionally, the findings from Han et al. suggest that interventions aimed at enhancing emotional intelligence could be particularly beneficial for non-clinical healthcare staff (12). Their study indicated that emotional intelligence not only directly reduced burnout but also moderated the relationship between job stress and burnout. This highlights the potential value of emotional intelligence training as part of comprehensive stress management programs for administrative and other non-clinical staff in healthcare settings.

Discussion

Non-clinical staff play a vital role in the healthcare system, providing essential support services that enable the smooth operation of healthcare facilities and the delivery of high-quality patient care (42). Despite their crucial contributions, research on workplace stress for non-clinical members of the healthcare workforce has been limited, especially compared to the volume of studies that have focused on the impact of similar stressors on clinical members of the workforce such as nurses and physicians (41). This lack of attention is concerning, as the findings of this review demonstrate that non-clinical staff experience significant stress-contributing factors and adverse consequences on their well-being and job satisfaction.

The identified stressors, such as workload burden, lack of control, dissatisfaction with rewards, unfair treatment, and difficulties in establishing supportive relationships, can have far-reaching implications for non-clinical staff and ultimately, the healthcare system. Chronic exposure to excessive job demands may lead to burnout, depression, anxiety, and emotional distress among non-clinical staff. These mental health challenges can result in individual impacts, such as absenteeism, presenteeism, cognitive impairment, and turnover intentions (43,44). The consequences not only affect the individual staff members but also have the potential to disrupt the continuity and quality of support services, ultimately impacting patient care and the overall functioning of healthcare facilities (45).

Explanations of findings

As highlighted in our results, the COVID-19 pandemic has further exacerbated the challenges faced by non-clinical healthcare staff, exposing them to additional stressors such as increased workload, rapidly changing work environments, and heightened occupational health and safety concerns (46). The pandemic has also underscored the essential role of non-clinical staff in maintaining the resilience and adaptability of the healthcare system during crises (47). As such, it is crucial to prioritize the well-being and support of non-clinical staff to ensure their ability to continue providing vital services in the face of future challenges.

While our review primarily focused on psychological impacts of workplace stress, it’s important to consider potential physiological consequences as well. Although not directly observed in our included studies, research in other occupations and settings has shown that chronic workplace stress can lead to physiological dysregulation. These effects, such as disrupted sleep, appetite changes, headaches, and gastrointestinal issues, could also apply to non-clinical healthcare staff given some of the similarities in stress experiences (48,49).

Cynicism, lack of empathy, absenteeism, and presenteeism impact job performance and quality of work completed (50,51). These impacts jeopardize the well-being of non-clinical staff while undermining organizational capacity and resilience (52,53).

The JD-R theory provides a valuable framework for interpreting the results of this review. According to this theory, the balance between job demands and job resources plays a crucial role in employee well-being and organizational outcomes (54). Our findings strongly support this theory and we have integrated it into our conceptual model (Figure 2). The stressors identified in our review, such as workload burden and lack of control, align with the concept of job demands in the JD-R theory. Conversely, factors like supportive leadership and autonomy represent job resources that can potentially mitigate the impact of these demands. This theoretical alignment underscores the importance of addressing both the reduction of job demands and the enhancement of job resources in efforts to improve the well-being of non-clinical healthcare staff.

Implications for future action

Enhancing autonomy and support for non-clinical staff can not only improve their well-being but also potentially have broader implications for the quality-of-care delivery. While direct evidence for non-clinical staff is limited, providing these staff members with greater autonomy and control over their work could theoretically contribute to improved organizational performance. However, further research is needed to establish this relationship definitively.

Our conceptual model (Figure 2) suggests that targeted interventions such as stress management programs, supportive leadership initiatives, and efforts to foster a positive work environment could be beneficial for non-clinical healthcare staff. By enhancing job resources, these interventions could potentially moderate the effects of job demands on non-clinical staff mental health and individual impacts (55).

Enhancing job resources such as work control, recognition and reward systems, and fair treatment practices could serve as effective interventions to buffer the impact of high job demands on non-clinical healthcare staff. These resources not only directly improve job satisfaction but also provide staff with the means to better cope with the challenges of their roles (56). Our model highlights how these interventions, focusing on job resources, could potentially moderate the effects of job demands on non-clinical staff mental health and individual impacts.

While direct evidence for non-clinical staff is limited, we hypothesize that providing these staff members with greater autonomy and control over their work could potentially contribute to improved organizational performance. However, further research is needed to establish this relationship definitively and to explore any potential indirect effects on patient outcomes.

This non-clinical workforce is pivotal to ensuring the entire system—from medical records to facilities operations to revenue cycle management—functions optimally and continually improve (57). Their burn-out and attrition perpetuate vicious cycles of understaffing, overwork, suboptimal care, and organizational instability as illustrated in Figure 2. Proactive, evidence-based efforts to cultivate their resilience must become a strategic priority (58).

Our findings on workplace stress factors among non-clinical healthcare staff show notable similarities to research conducted in other professional fields, such as education, corporate environments, and public service. This alignment suggests that while healthcare settings have unique challenges, many workplace stress factors are common across various sectors.

The parallels between our findings and those from other fields present an opportunity for cross-sector learning. The healthcare industry could potentially benefit from stress management strategies and interventions that have proven effective in other professional contexts. This cross-pollination of ideas could accelerate the development of effective stress reduction programs for non-clinical healthcare staff.

Our conceptual model underscores that a multi-pronged approach will likely be required, addressing systemic issues affecting job resources, such as supportive leadership, peer support, work-life policies, and training development (48). Moreover, although existing research is limited, the variations in stress experiences among different subgroups of non-clinical staff highlight the likely need for tailored interventions that address the specific challenges faced by each group (32). Failure to recognize and address these distinct needs may perpetuate inequities and hinder the effectiveness of support services within the healthcare system (48).

Researchers and healthcare administrators can use our model to identify key areas for intervention, anticipate potential outcomes, recognize complex relationships between factors, and design comprehensive strategies addressing both personal and organizational impacts. As demonstrated in previous research, such conceptual models can evolve as new evidence emerges. We encourage future studies to build upon and refine this model, potentially expanding it to include more specific interventions and their targeted outcomes.

Limitations and future research directions

While this review provides valuable insights into workplace stress among non-clinical healthcare staff, it is important to acknowledge the limitations of the current literature: (I) scarcity of targeted research focusing specifically on non-clinical staff limits the depth and breadth of the conclusions. (II) Heterogeneity of the non-clinical workforce poses challenges in drawing generalizable conclusions due to inconsistent delineation of specific roles and responsibilities. (III) Cross-sectional design of most studies limits the ability to establish causal relationships between stressors and outcomes. Longitudinal studies are needed to understand the long-term impact of chronic stress. (IV) Reliance on self-reported measures may introduce bias and limit objectivity. Future research should incorporate objective stress measures and triangulate data from multiple sources. (V) Limited evidence on tailored interventions for non-clinical staff highlights the need for more research to explore the effectiveness of potential strategies in this specific context. (VI) Cultural, organizational, and language limitations: the results of experienced stress factors by non-clinical healthcare workers may be significantly influenced by cultural factors and the way hospitals and healthcare systems are organized, which can vary considerably from country to country. While our review included studies from diverse geographical locations, providing a broad perspective, this diversity may also introduce variability in findings due to these cultural and organizational differences. Additionally, our inclusion of only English-language articles may have limited our ability to capture the full range of international perspectives on this topic, potentially impacting the generalizability of our findings to non-English speaking contexts. Future studies could benefit from including non-English publications and focusing on specific regional contexts to address these limitations.

By addressing the limitations identified in this review, future research can provide a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of workplace stress among non-clinical healthcare staff. Longitudinal studies are needed to establish causal relationships between stressors and outcomes, while the incorporation of objective stress measures could complement self-reported data. Exploration of tailored interventions specifically designed for non-clinical staff is crucial, as is the investigation of variations in stress experiences among different subgroups of this workforce to develop more targeted support strategies. Additionally, future studies could explore comparative analyses between clinical and non-clinical staff stressors and their respective impacts on patient care, providing insights into workplace stress across the entire healthcare workforce and potentially informing holistic interventions. These research directions aim to inform evidence-based interventions and policies that promote the well-being and job satisfaction of this essential workforce, ultimately contributing to enhancing the overall resilience and effectiveness of healthcare organizations.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this narrative review assessed the sources and impacts of workplace stress experienced by non-clinical healthcare staff. Our findings highlight the pressing need to acknowledge and address this workplace stress, as it significantly affects both individual well-being and organizational performance. Investing in research and interventions tailored to the needs of non-clinical staff is essential to foster a supportive and resilient healthcare system that can effectively meet the challenges of the future.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the Narrative Review reporting checklist. Available at https://jhmhp.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jhmhp-24-88/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://jhmhp.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jhmhp-24-88/prf

Funding: None.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jhmhp.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jhmhp-24-88/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Burman R, Goswami TG. A Systematic Literature Review of Work Stress. Int J Manag Stud 2018;3:112-32. [Crossref]

- Bhui K, Dinos S, Galant-Miecznikowska M, et al. Perceptions of work stress causes and effective interventions in employees working in public, private and non-governmental organisations: a qualitative study. BJPsych Bull 2016;40:318-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Blom V, Kallings LV, Ekblom B, et al. Self-Reported General Health, Overall and Work-Related Stress, Loneliness, and Sleeping Problems in 335,625 Swedish Adults from 2000 to 2016. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:511. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gilles I, Burnand B, Peytremann-Bridevaux I. Factors associated with healthcare professionals' intent to stay in hospital: a comparison across five occupational categories. Int J Qual Health Care 2014;26:158-66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Colligan TW, Higgins EM. Workplace stress: Etiology and consequences. Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health 2006;21:89-97. [Crossref]

- Lukan J, Bolliger L, Pauwels NS, et al. Work environment risk factors causing day-to-day stress in occupational settings: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2022;22:240. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Maulik PK. Workplace stress: A neglected aspect of mental health wellbeing. Indian J Med Res 2017;146:441-4. [PubMed]

- Batson J. Workplace Stress - the American Institute of Stress [Internet]. The American Institute of Stress. 2021 [cited 2023 May 4]. Available online: https://www.stress.org/workplace-stress

- Akanji B. Occupational Stress: A Review on Conceptualisations, Causes and Cure. Economic Insights – Trends and Challenges 2013;II:73-80.

- Maiti D, Nath S. Occupational Stress – A Matter of Concern in the Present Era: An Overview. Economy and Innovation 2023;36:226-31.

- González-Rico P, Guerrero-Barona E, Chambel MJ, et al. Well-Being at Work: Burnout and Engagement Profiles of University Workers. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022;19:15436. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Han W, Kim J, Park J, et al. Influential Effects of Emotional Intelligence on the Relationship between Job Stress and Burnout among General Hospital Administrative Staff. Healthcare (Basel) 2022;10:194. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lanctôt N, Guay S. The aftermath of workplace violence among healthcare workers: A systematic literature review of the consequences. Aggress Violent Behav 2014;19:492-501. [Crossref]

- Caruso CC. Negative impacts of shiftwork and long work hours. Rehabil Nurs 2014;39:16-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Muñoz S, Iglesias CÁ, Mayora O, et al. Prediction of stress levels in the workplace using surrounding stress. Information Processing & Management 2022;59:103064. [Crossref]

- Boitet LM, Meese KA, Hays MM, et al. Burnout, Moral Distress, and Compassion Fatigue as Correlates of Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms in Clinical and Nonclinical Healthcare Workers. J Healthc Manag 2023;68:427-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gaur S, Saminathan J. Study report on work life imbalance impact on job satisfaction in non-clinical staff at tertiary health care center, Delhi. Clin Pract 2018;15:881-6.

- Dev Arya K, Tagore P, Hari P, et al. A comparative study among clinical and non-clinical medical professional's experiences perceived stress during Covid -19 pandemic era, at tertiary health care centre in central India. Int J Health Clin Res 2021;4:31-4.

- Ravalier JM, McVicar A, Boichat C. Work Stress in NHS Employees: A Mixed-Methods Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:6464. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Green BN, Johnson CD, Adams A. Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: secrets of the trade. J Chiropr Med 2006;5:101-17. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 2005;15:1277-88. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs 2008;62:107-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, et al. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:117. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Adamis D, Minihan E, Hannan N, et al. Burnout in mental health services in Ireland during the COVID-19 pandemic. BJPsych Open 2023;9:e177. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rotenstein LS, Brown R, Sinsky C, et al. The Association of Work Overload with Burnout and Intent to Leave the Job Across the Healthcare Workforce During COVID-19. J Gen Intern Med 2023;38:1920-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim NM, Gamal-Elden DA, Gadallah MA, et al. Emotional distress symptoms and their determinants: screening of non-clinical hospital staff in an Egyptian University hospital. BMC Psychiatry 2022;22:793. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pala AN, Chuang JC, Chien A, et al. Depression, anxiety, and burnout among hospital workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One 2022;17:e0276861. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jones A, Zhang S, Woodburn A, et al. Experiences of staff working in a mental health trust during the COVID-19 pandemic and appraisal of staff support services. Int J Workplace Health Manag 2022;15:154-73. [Crossref]

- Brady C, Shackleton E, Fenton C, et al. Worsening of mental health outcomes in nursing home staff during the COVID-19 pandemic in Ireland. PLoS One 2023;18:e0291988. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Edwards ST, Marino M, Balasubramanian BA, et al. Burnout Among Physicians, Advanced Practice Clinicians and Staff in Smaller Primary Care Practices. J Gen Intern Med 2018;33:2138-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Norman J, Basu S. Evaluating an intervention addressing stress in emergency department clerical staff. Occup Med (Lond) 2018;68:638-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Donovan S, Duncan J, Patterson S. Risky business: Qualitative study of exposure to hazards and perceived safety of non-clinical staff working in mental health services. Int J Workplace Health Manag 2018;11:177-88. [Crossref]

- Grant A, Kontak J, Jeffers E, et al. Barriers and enablers to implementing interprofessional primary care teams: a narrative review of the literature using the consolidated framework for implementation research. BMC Prim Care 2024;25:25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jabareen Y. Building a conceptual framework: philosophy, definitions, and procedure. Int J Qual Methods 2009;8:49-62. [Crossref]

- Imenda S. Is there a conceptual difference between theoretical and conceptual frameworks? J Soc Sci 2014;38:185-95. [Crossref]

- Bakker AB, Demerouti E. The Job Demands-Resources model: state of the art. J Manag Psychol 2007;22:309-28. [Crossref]

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77-101. [Crossref]

- Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nurs 2005;52:546-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldana J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. 3rd ed. SAGE Publications; 2014.

- Whetten DA. What constitutes a theoretical contribution? Acad Manage Rev 1989;14:490-5. [Crossref]

- van Dijk DM, van Rhenen W, Murre JMJ, et al. Cognitive functioning, sleep quality, and work performance in non-clinical burnout: The role of working memory. PLoS One 2020;15:e0231906. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dewa CS, Loong D, Bonato S, et al. The relationship between physician burnout and quality of healthcare in terms of safety and acceptability: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2017;7:e015141. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD, Sinsky CA, et al. Burnout Among Health Care Professionals: A Call to Explore and Address This Underrecognized Threat to Safe, High-Quality Care. NAM Perspect 2017; [Crossref]

- Hall LH, Johnson J, Watt I, et al. Healthcare Staff Wellbeing, Burnout, and Patient Safety: A Systematic Review. PLoS One 2016;11:e0159015. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Basu S, Yap C, Mason S. Examining the sources of occupational stress in an emergency department. Occup Med (Lond) 2016;66:737-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shaukat N, Ali DM, Razzak J. Physical and mental health impacts of COVID-19 on healthcare workers: a scoping review. Int J Emerg Med 2020;13:40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Adams JG, Walls RM. Supporting the Health Care Workforce During the COVID-19 Global Epidemic. JAMA 2020;323:1439-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Panagioti M, Panagopoulou E, Bower P, et al. Controlled Interventions to Reduce Burnout in Physicians: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177:195-205. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fernandes A, Moreira LMA, Santos APMV, et al. Factors associated with stress, anxiety and depression among health professionals: a cross-sectional study. Cien Saude Colet 2022;27:375-85.

- Harnois G, Gabriel P. Mental health and work: Impact, issues and good practices. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000.

- Ferrara P, Albano L. The impact of COVID-19 on healthcare workers in Italy: beyond the infection. J Endocrinol Invest 2020;43:1415-6.

- Deligkaris P, Panagopoulou E, Montgomery AJ, et al. Job burnout and cognitive functioning: A systematic review. Work Stress 2014;28:107-23.

- Bakker AB, Demerouti E. Job demands-resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. J Occup Health Psychol 2017;22:273-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chrouser KL, Partin MR, Gainsburg I, et al. Examining the surgical stress effects (SSE) framework in practice: A qualitative assessment of perceived sources and consequences of intraoperative stress in surgical teams. Am J Surg 2024;228:133-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Greenberg N, Docherty M, Gnanapragasam S, et al. Managing mental health challenges faced by healthcare workers during covid-19 pandemic. BMJ 2020;368:m1211. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Robertson HD, Elliott AM, Burton C, et al. Resilience of primary healthcare professionals: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract 2016;66:e423-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ruotsalainen JH, Verbeek JH, Mariné A, et al. Preventing occupational stress in healthcare workers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;2015:CD002892. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med 2014;12:573-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Bucala M, Vyas J, Ameling J, Jordan K, Lukela J, Chrouser K. A narrative review, qualitative analysis and development of a conceptual model of workplace stress factors among non-clinical healthcare staff. J Hosp Manag Health Policy 2025;9:10.