Are “all or nothing” contracts by hospital systems anti-competitive?—evidence from a recent antitrust lawsuit

Introduction

Hospital care accounts for a significant portion of U.S. healthcare expenditures, and research has consistently shown that hospital prices are a major driver of the high and increasing costs within the U.S. healthcare system (1). Hospital prices for commercially insured individuals result from negotiations between hospitals and commercial health plans and are generally subject to market forces. The expansion of multi-hospital systems (single organizations consisting of and controlling multiple hospitals) across the U.S., which by 2020 included more than two-thirds of all community hospitals, has drawn increasing attention as a potential source of market power that can drive up prices (2). Multiple studies have found that, even after adjusting for various factors, hospitals within multi-hospital systems command higher prices. These systems’ ability to negotiate higher prices for their member hospitals, and the specific mechanisms used, have remained largely unexplored due to the confidential nature of contract negotiations and the lack of public disclosure.

A growing body of research suggests that hospitals within multi-hospital systems have higher prices, even after accounting for other factors that may affect hospital prices. Lewis and Pflum [2017] found that hospitals targeted in cross-market mergers, resulting in multi-geographic market systems, experienced price increases of up to 33% when acquired by large systems (3). Schmitt [2018] found that increased contact between hospital systems and payers was associated with 6–7% higher hospital prices (4). Dafny and colleagues [2019] reported 7–10% price increases for hospitals involved in cross-market acquisitions within the same state (5). A more recent study by Andreyeva and colleagues [2022] estimated a 5% price increase for independent hospitals transitioning to system ownership (6). Despite the consistency of the findings associating systems status with higher prices, the exact mechanisms enabling hospitals to negotiate higher prices within systems remain unclear. Researchers have had limited ability to investigate potentially anti-competitive contracting practices due to confidential contract negotiations and the lack of public disclosure of contract terms.

Sidibe vs. Sutter Health anti-trust lawsuit (7)

A group of businesses and individuals filed a private antitrust lawsuit against Sutter Health, a dominant multi-hospital system in Northern California. They claimed that Sutter’s implementation of mandatory systemwide contracts with anticompetitive terms led to inflated health insurance premiums for class members. Initially filed in 2012, the lawsuit sought $400+ million in damages ($1.2 billion after trebling). The plaintiffs argued that Sutter Health violated antitrust laws by bundling inpatient services across all member hospitals and imposing anti-competitive terms within their contracts, hindering insurers from directing patients to lower-cost options. Sutter Health had previously settled a similar case brought by a different group of plaintiffs and the California Attorney General (8). The second case (Sidibe vs. Sutter Health) proceeded to trial, and a federal jury issued a verdict in favor of Sutter Health in March 2022 (9). The plaintiffs filed an appeal, arguing that the court’s exclusion of evidence covering the period before 2006 was a mistake and that this evidence was crucial in documenting and understanding Sutter’s anticompetitive behavior (10). Previously confidential information included in the appeals documents revealed that during the 1990s, insurers negotiated with Sutter hospitals individually, but in the early 2000s, Sutter began demanding systemwide “all-or-nothing” contracts (11). This study incorporates this previously confidential information to investigate how “all-or-nothing” contracting affected competition and prices at Sutter system hospitals (12).

Our study incorporates previously confidential qualitative information from this major hospital antitrust lawsuit (Sidibe vs. Sutter Health) to document the timing of the adoption of and quantify the impact of “all-or-nothing” contracting by Sutter Health, a significant multi-hospital system in Northern California. This paper aims to document how such contracting practices can affect competitive dynamics and prices within hospital markets in the U.S.

Data and methods

In the following sections, we summarize the data sources, hospitals included in the study sample, and study methods. Please see Appendix 1 for a more detailed discussion of these topics.

Data and study sample

Data

This study combines qualitative and quantitative data. Importantly, we draw on recently available public court records from the Sutter-Sidibe case, including the original trial and recent appeals court hearings, to determine the timing of the Sutter system’s introduction and adoption of specific, potentially anti-competitive contracting practices. This information is used to determine the pre- and post-periods for our analyses. Data on hospital prices, utilization, and other hospital characteristics are drawn from California’s Department of Health Care Access and Information [HCAI; formerly named California Office of Health Planning and Development (OSHPD)]. Additional quantitative data are drawn from two Federal Government Agencies: the Agency on Health Care Research and Quality (AHRQ), and the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).

Sample

Our study focuses on the effects of “all-or-nothing” contracting by Sutter system hospitals within the context of contracting for general acute care hospital services (as opposed to narrowly focused specialty hospitals). As such, we limit our sample to general acute care hospitals, including Sutter hospitals and all other non-Sutter general acute care hospitals that are comparable to Sutter system member hospitals. We exclude the following types of hospitals: psychiatric and behavioral health, long-term care, rehabilitation, and all Kaiser general acute care hospitals (as their reporting to HCAI is limited during the study period).

Methods

Overview

Our analysis is structured to answer two interrelated questions regarding the potential effects of Sutter’s imposition of “all-or-nothing” contracting, including:

- How do Sutter’s prices compare to prices in control group hospitals before and after Sutter imposed “all-or-nothing” contracting terms (after controlling for other factors that affect prices)?

- Were Sutter hospitals’ prices subject to competitive market pressure before introducing “all-or-nothing” contracting (pre-period) and, if so, did the effects of competition on Sutter hospital prices change in the post-periods (i.e., were Sutter hospitals shielded from competitive market pressure in setting their prices in the post-periods)?

We use a pre-post/control-treatment design to test for Sutter differences compared to control group hospitals in competition and price effects 5 years immediately before and after Sutter implemented “all-or-nothing” contracting. We also performed an analysis for a second post-period covering 2010–2019 to test whether any observed effects in the first post-period continued over the long run. The second post-period analysis included more recently available hospital quality data unavailable for earlier periods.

We conducted a statistical (regression) analysis to control for price differences between Sutter and control group hospitals that are driven by differences in the underlying characteristics of Sutter hospitals compared to control group hospitals, irrespective of their membership in the Sutter system. For example, if Sutter hospitals serve patients with higher case mix complexity compared to control group hospitals, we would expect their prices to be higher to reflect this factor than control group prices, independently from their membership in the Sutter system and Sutter’s introduction of “all-or-nothing” contracting.

The statistical model was applied to all comparable general acute care hospitals to control for a wide range of factors, including hospital ownership and type, membership in other non-Sutter systems, hospital size, payor mix, complexity of hospital services, and local market competition. Time variables are included to capture industry-wide effects of new technology, quality, and other changes that may have occurred during the study period affecting all hospitals. Our statistical analysis controls for these factors to provide an estimate of the price and competitive differences between Sutter hospitals and control group hospitals in post periods derived from their membership in the Sutter system and Sutter’s adoption of anti-competitive practices.

Construction of pre-post and periods treatment and control groups

We construct three time periods: a pre-period (1995–1999) and two post-periods: post-period 1 (2001–2005) and post-period 2 (2010–2019). We code the total sample of comparable general acute care hospitals into treatment and control groups. Our treatment group hospitals include all Sutter member hospitals as reported and defined by HCAI data each year. Our primary control group of hospitals includes all other non-Sutter general acute care hospitals. However, within the control group, we estimated separate price and competition effects for hospitals that were members of the Dignity Health System, the largest multi-hospital system in the state. Media reports from early 2000 suggest that the Dignity system may have also implemented “all-or-nothing” contracting for its system members (13). The hospital sample sizes for each of the periods are as follows: pre-period (Sutter: n=13, control: n=197); post-period 1 (Sutter: n=21, control: n=182) and post-period 2 (Sutter: n=21, control: n=179). The Results section below summarizes findings comparing Sutter hospitals with the primary control group hospitals after controlling for hospitals in the Dignity system. A full set of descriptive statistics and regression findings are included in Appendix 1.

Construction of key measures

Hospital prices

Hospital prices are constructed in several steps. We begin with a standard price measure constructed by HCAI referred to as Net Revenue per Adjusted Inpatient Admission for all commercial payors (other third party on HCIA Forms). This is a broad price measure that covers both inpatient and outpatient services. Next, to make the price measure comparable across different hospitals it is adjusted for the two most important cost drivers: case mix severity of patient medical conditions as well as the differences in cost of labor for hospitals located in different geographic areas. To make this adjustment Net Revenue per Admission is divided by each hospital’s commercial payor inpatient case mix index and the local area wage index in each year.

Hospital market competition

We construct the Herfindahl-Hirschman index (HHI), a standard measure of market structure (concentration), to measure the competitiveness of each hospital’s market structure for each year. Importantly, we compute a system-based (HHI-system) for each hospital that takes into account whether each hospital is part of a system and, if so, takes into account the degree of overlap of their geographic markets to calculate the HHI for each hospital. Each hospital’s geographic market is based on the zip codes that a hospital draws from (up to 20) and we calculate the HHI value for each zip code. Hospitals that are part of the same system are assigned the same hospital ID in determining geographic markets and calculating market shares. When there is no overlap in a geographic market between a hospital and its system members, the HHI-system value is equal to the HHI-hospital value (as if not a member of a system). When there is geographic overlap between system members, their HHI will change as well as the HHI levels of their competitors. A hospital’s HHI is then calculated as a sum of the zip code HHI values, giving each zip code a weight proportional to the number of patients coming from that zip code. Zip code level HHI is calculated as the sum of the squared market shares of competing hospitals serving the zip code. Zip code level data for the calculation of HHIs are drawn from OSHPD’s Patient Discharge Data files. HHI values from near zero to 1.0, with higher HHI values representing more concentrated, less competitive markets.

Calculation of the competition and price differences between Sutter hospitals and control group hospitals

We hypothesize that the adoption of “all-or-nothing” contracting by the Sutter system changed how competition affected prices at Sutter hospitals but not at control group hospitals, and that as a result, price differences between Sutter hospitals and control group hospitals will increase. The model controls for and calculates the average effects of all the factors across all hospitals including Sutter and control group hospitals except that it allows for differential effects for prices and competition before and after the adoption of “all-or-nothing” contracting by the Sutter system. We apply results from the statistical model to calculate the before and after differences in the effects of competition on prices for Sutter and control group hospitals based on the HHI values for each Sutter hospital in each year and we sum these price differences across all Sutter hospitals to estimate the overall difference in prices between Sutter and the average across all control group hospitals in each period. A detailed description of the calculation methods is included in Appendix 1.

Results

This section summarizes the key findings related to Sutter’s prices and the effects of competition on Sutter’s prices. The full set of regression results is included in Appendix 1.

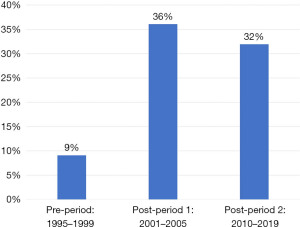

Figure 1 presents the findings comparing prices at Sutter hospitals to prices at control group hospitals before and after Sutter’s implementation of “all-or-nothing” contracting practices. In the pre-period, both groups have higher prices in less competitive markets. Sutter prices are estimated to be 9% higher than prices in control group hospitals. This indicates that prices at Sutter hospitals in the pre-period were similar to prices in control hospitals.

The estimated price differences between Sutter hospitals and control group hospitals in the two post-periods increased substantially. Prices at Sutter hospitals are much higher than prices in control group hospitals with estimated differences reaching +36% in post-period 1 and +32% in post-period 2.

These results indicate that Sutter’s prices increased substantially and significantly relative to control group hospital prices after Sutter implemented “all-or-nothing” contracting practices. Importantly, these results summarize net price differences between the Sutter and control group hospitals after statistically controlling for a wide range of other factors that affect hospital prices.

Figure 2 summarizes results that examine changes in the relationship between competition and hospital prices for Sutter hospitals and control group hospitals in the pre- and post-periods. In the pre-period (1995–1999), both Sutter and control hospitals experienced positive effects of competition—prices are higher in less competitive markets.

A 1,000-point difference in HHI in control group hospitals resulted in a 5.1% change in prices while Sutter hospital prices increased by 4.3% when HHI increased 1,000 points. This indicates that prices were higher in less competitive markets and lower in more competitive ones for both Sutter and control group hospitals.

In post-periods 1 and 2 the competitive effects on control hospitals remained positive and strengthened, indicating that competition had a stronger impact on prices in the post-periods compared to the pre-period. A 1,000-point difference in HHI would lead to price differences of 9.7% and 10.3% in control group hospitals in the two post-periods.

This relationship did not hold for hospitals within the Sutter system.

The relationship between competition and prices for Sutter hospitals not only weakened but reversed direction in the post-periods. For example, prices at Sutter hospitals in post-period 1 with HHI values of 4,000 are estimated to be +4.3% higher than Sutter hospitals with HHI values of 5,000. These findings suggest that Sutter hospitals were no longer held in check by local market competition, and Sutter hospitals in more competitive markets could raise their prices to levels above prices in less competitive markets.

Discussion

There is a growing consensus by policy analysts and researchers that the growth of multi-hospital systems, including those where system members may not be in the same or overlapping geographic markets, requires increased scrutiny and possibly regulation because of their potential ability to attain and exercise market power in negotiating anticompetitive contracts with commercial health plans (14-16). Our findings, based on previously protected confidential information combined with empirical data, provide evidence to support these concerns.

The results show that prior to the implementation of “all-or-nothing” contracts in the early 2000s, the prices charged by Sutter member hospitals were kept in check by competitive market forces, and they were comparable to the prices charged by hospitals in the control group. However, after adopting the “all-or-nothing” contracting strategy, Sutter’s prices were no longer restrained by competitive pressures. As a result, their prices surged and remained significantly higher, approximately 30% above the prices charged by hospitals in the control group. The absence of competitive market forces allowed Sutter to raise and maintain elevated prices after introducing the “all-or-nothing” contracts.

The argument for increased regulation is that some multi-hospital systems can demand “all-or-nothing” contracts from commercial health plans if their systems are large or concentrated enough in one geographic region, and/or have essential “must-have” member hospitals that can be used to require that all member hospitals be included in the health plans approved provider network and that they can also demand higher payment rates for the entire network or none at all.

This leaves the commercial health plans with two poor choices—to include all the system’s member hospitals, including those with prices well above competitive market levels, or risk losing all of the member hospitals. The loss of all system member hospitals could undermine the commercial viability of the commercial health plan’s health insurance product if it did not include essential hospitals or enough hospital providers in a given geographic area. In some cases, due to network adequacy laws and regulations, some services or providers are considered “must-haves”, such as hospitals with maternity services, neonatal intensive care units, or trauma center designation, for a health plan to offer a commercially viable provider network. Health plans may have to contract with a system to ensure their provider networks meet regulatory requirements. In sum, by tying all member hospitals together and negotiating on a systemwide basis, a health system can increase prices above competitive market levels for its member hospitals.

Our study results show that Sutter system hospitals had been contracting individually with health plans but then were able to tie all their member hospitals together in the early 2000s to begin demanding “all-or-nothing” contracts. This change shielded them from pre-period competitive pressure on their prices and allowed them to obtain substantially higher prices compared to control group prices in the post-periods after controlling for a wide range of factors that also affect prices.

A related concern is that once a system can effectively demand “all-or-nothing” contracts, it can then modify and update its contracts over time with additional anticompetitive terms that protect and expand its systemwide market power into the future. The Sutter-Sidibe case record provides evidence of this type of behavior. Health plans, to reduce the anticompetitive effects of “all-or-nothing” contracts, can develop tiered network products that do accede to system demands to include all system member hospitals in the contracted provider network but within these tiered products categorize providers into tiers based on their pricing and quality to steer patients to non-system member hospitals that provide lower prices and higher-value care. The Sutter-Sidibe case record shows that Sutter leveraged their “all-or-nothing” contracting power to amend their contracts over time with health plans to add anti-tiering/anti-steering clauses. Another anticompetitive practice revealed in this lawsuit was the addition of contract language over time by Sutter to prohibit health plans from sharing pricing data that might be used to enable patients and employers to make informed decisions regarding healthcare providers, both for individual medical services and network participation.

Conclusions

This study provides findings on an important health policy issue at a critical point in time. While there is growing consensus that the growth of multi-hospital systems has contributed to rising hospital prices and health spending, direct evidence on specific anti-competitive methods and practices has been lacking. Multiple states and federal policymakers are proposing new efforts to regulate anti-competitive behaviors by hospitals and other provider groups. However, the language supporting these policies targeting anticompetitive practices has remained general due to the lack of research and specific evidence. For example, at the federal level, recently introduced (Sept 2023) legislation (S2840, Bipartisan Primary Care and Health Workforce Act) calls for a ban of “anticompetitive terms in contracts between hospitals and insurers” without defining specific anticompetitive terms and/or practices (17).

This study provides a factual and empirical basis for constructing a more detailed roadmap for policymakers and regulators to target and eliminate specific anticompetitive practices to protect and restore competitive forces in our healthcare system. For example, blocking potentially anticompetitive transactions entirely or approving transactions with conditions such as prohibiting “all-or-nothing” contracting can help states maintain any competitive forces present in the market. Applying conditions to approved transactions may allow state officials to oversee and govern the behavior of providers post-transaction while states pursue other legislative and regulatory policies. Although the use of conditions is a growing approach at the state level, little research has been done to explore its effectiveness and potential application to other states. More research is needed to gain a better understanding of the threats to competition in healthcare markets to develop policies that will protect and restore competition.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was funded in part by

Footnote

Peer Review File: Available at https://jhmhp.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jhmhp-24-59/prf

Conflicts of Interest: Both authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jhmhp.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jhmhp-24-59/coif). G.M. reports that this study was funded in part by Arnold Ventures (No. GR-64591); and received grants from Arnold Ventures and California HealthCare Foundation, outside the submitted work. The other author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Turner A, Miller G, Lowry E. High U.S. Health Care Spending: Where Is It All Going? 2023. Available online: http://dx.doi.org/

10.26099/r6j5-6e66 - American Hospital Association. Fast Facts on U.S. Hospitals, 2023. Available online: https://www.aha.org/statistics/fast-facts-us-hospitals

- Lewis MS, Pflum KE. Hospital systems and bargaining power: evidence from out-of-market acquisitions. The RAND Journal of Economics 2017;48:579-610. [Crossref]

- Schmitt M. Multimarket contact in the hospital industry. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 2018;10:361-87. [Crossref]

- Dafny L, Ho K, Lee RS. The price effects of cross-market mergers: theory and evidence from the hospital industry. The RAND Journal of Economics 2019;50:286-325. [Crossref]

Andreyeva E Gupta A Ishitani CE The corporatization of hospital care. 2022 . Available online:10.2139/ssrn.4134007 - Case Summary: Sidibe-v-Sutter-Health. Available online: https://sourceonhealthcare.org/article/case-summary-sidibe-v-sutter-health/

Sutter Health Settlement with UEBT and the California Attorney General - Jury finds for Sutter Health in California antitrust trial. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/legal/transactional/jury-finds-sutter-health-california-antitrust-trial-2022-03-11/

Plaintiff Class Appeals Antitrust Decision in Sutter Health Case 2022 . Available online: https://constantinecannon.com/firm-news/plaintiff-class-appeals-antitrust-decision-in-sutter-health-case/- Djeneba Sidibe v. Sutter Health, Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. Available online: https://www.courtlistener.com/audio/87860/djeneba-sidibe-v-sutter-health/

- Gu AY. California District Court’s Exclusion of Evidence under Scrutiny as Ninth Circuit Hears Oral Arguments in the Appeal of Sidibe v. Sutter Health Class Action. 2023. Available online: https://sourceonhealthcare.org/california-district-courts-exclusion-of-evidence-under-scrutiny-as-ninth-circuit-hears-oral-arguments-in-the-appeal-of-sidibe-v-sutter-health-class-action/

- Blue Cross, Catholic hospitals make pact. Available online: https://www.recordnet.com/story/news/2000/08/16/blue-cross-catholic-hospitals-make/50794569007/

- Weighing Policy Trade-offs: Overview of NASHP’s Model Prohibiting Anticompetitive Contracting. Available online: https://nashp.org/weighing-policy-trade-offs-overview-of-nashps-model-prohibiting-anticompetitive-contracting/

- New bill aims to clamp down on hospital anti-competition tactics like 'all-or-nothing' contracts. Available online: https://www.fiercehealthcare.com/hospitals/new-bill-aims-to-clamp-down-hospital-anti-competition-tactics-like-all-or-nothing

- King JS, Montague AD, Arnold DR, et al. Antitrust's Healthcare Conundrum: Cross-Market Mergers and the Rise of System Power. Hastings Law Journal 2023. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4037747

- Bipartisan Primary Care and Health Workforce Act. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/118/bills/s2840/BILLS-118s2840is.pdf

Cite this article as: Melnick G, Fonkych K. Are “all or nothing” contracts by hospital systems anti-competitive?—evidence from a recent antitrust lawsuit. J Hosp Manag Health Policy 2024;8:21.