Ward Medicines Assistants: a new role to support nurses with medication-related tasks

Highlight box

Key findings

• Ward Medicines Assistants can complete medication-related tasks and provide nursing staff with additional time to care for patients.

• Medical and nursing staff perceived Ward Medicines Assistants are supportive and reduced cognitive burden.

What is known and what is new?

• Ward Medicines Assistants are pharmacy staff given additional training and supervision to adopt ward-based roles in clinical settings.

• These findings demonstrate Ward Medicines Assistants can release productivity by completing medication-related tasks in clinical settings.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• The findings demonstrate Ward Medicines Assistants may be able to contribute to reforming roles and retaining nursing staff by reducing cognitive burden and providing nurses with more time to care.

Introduction

Demand for high quality health care is expected to continue to increase over time. Existing evidence identifies this may be due to a combination of population growth and the increasing prevalence of chronic disease (1). Similar growth has also been observed in relation to the use of medications, as the ‘pharmaceuticalisation of society’ describes the phenomenon of ‘more people, using more medications’ (2). The increasing use of medications has increased demand for pharmaceutical care and access to pharmacy professionals, globally (3,4). However, increases in demand for access to highly-skilled workforce have led to shortages of healthcare professionals in many jurisdictions, including beyond the pharmacy team (5). Nursing shortages are widely reported (5,6) with workload and uncertainty dealing with new medications and complex treatments identified as a contributory factor to stress (7). The International Council of Nurses reported widespread concern relating to nursing workloads, burnout, stress and insufficient resources (6). Poor retention and recruitment of nurses, increases demands on the existing nursing workforce, which has been linked to reduced quality of care and patient safety (8). The intersection of increasing demand for pharmaceutical and nursing care has forced healthcare providers to consider alternative and supportive approaches to workforce deployment.

New approaches to staffing

Healthcare organisations in England have started to explore deploying non-registered pharmacy assistants beyond the physical stores and dispensary of the pharmacy, to inpatient hospital wards, in a much more patient facing role referred to as ‘Medicines Assistants’, ‘Ward Medicines Assistants’ or ‘WMAs’ (9,10). Non-registered pharmacy assistants typically support the procurement and supply of medicines, though are often non-patient facing, based in hospital medicines stores or dispensaries to support pharmacists and pharmacy technicians. An expansion of medication use over the 20th century has increased the demand for clinical pharmacy services (3), leading to an extension of the role of pharmacy technicians, pharmacists, and more recently, non-registered pharmacy assistants (4,11). The adaptation of pharmacy assistants into WMAs has primarily focused on their place of work, moving from the dispensary or pharmacy store to inpatient wards, to work alongside nurses, doctors and healthcare assistants. This shift in environment, facilitated the development of role descriptors using expertise from key stakeholders from across nursing, medical, pharmacy and human resource professionals (see Table 1) (9). However, these are new posts and the full extent of the scope of the role as it matures is yet to be defined. Appointed to standardised national pay scales in the English National Health Service, WMAs are paid approximately £11.11 per hour and given bespoke training that combined pharmacy assistant and healthcare assistant education, for example about medication counselling, supporting medication supply, gathering items for intravenous medication use and second checking the administration of Schedule 2 and 3 controlled drugs.

Table 1

| Task | Activity |

|---|---|

| Help nursing staff during medication administration rounds | Getting medicines ready to administer |

| Sourcing medicines from other wards or pharmacy | |

| Assisting patients to take their medicines | |

| Second checking Schedule 2 and 3 controlled drugs | |

| Gathering items for nurses to administer intravenous medications | |

| Ensuring discharge medication supply ready on time | Communicating with prescribers to write prescriptions |

| Helping to order or collect medicines from pharmacy | |

| Liaising with community pharmacy for post-discharge supply | |

| Counselling patients about how to use medications | |

| Information communication | Attending handovers, ward-rounds and multidisciplinary team meetings |

| Highlighting patients on critical medications, such as intravenous antibiotics | |

| Answering queries from other members of staff | |

| Inpatient medication supply | Ensuring the ward has enough stock for over the weekend |

| Ensuring individual patients have enough medications for over the weekend | |

| Waste | Identifying and processing medications for re-use |

| Destroying waste medication which cannot be re-used |

Baqir et al. demonstrated WMAs can make medicines use safer by reducing unintended omitted doses (UODs). UODs describe an occurrence when a medication is prescribed but the administration is missed unintentionally (e.g., due to nature and scale of staff workload). UOD rate in the intervention group, where WMAs supported nurses with medicines administration, was 1.1% (2 patients) compared with 18.5% (68 patients) in the control group [P<0.0001; 95% confidence interval (CI): −0.396 to −0.225] (10). Other work, explored the role of WMAs further, concluding they support medication administration rounds, saving on average 17.5 hours of nurse-led medicines-related work per-ward-per-week, thus contributing to saving nursing time (9). The team also found that WMAs acted as a conduit between nursing and pharmacy professionals, improving communications about medicines use on the ward. However, existing work has not explored levels of awareness of the role beyond nursing staff, such as with senior nurses such as matrons, junior doctors (non-Consultant medics), and senior doctors (Consultant medics). Additionally, existing work was completed relatively early as part of the development and deployment of the role, where WMAs worked on specific wards rather than being deployed across the organisation universally at scale in all inpatient wards. Further work is therefore needed to explore how WMAs have embedded into teams when they are deployed universally across inpatient wards to identify levels of awareness and perceived impact on productivity for staff.

Aim

To explore medical and nursing staff awareness of WMAs and the perceived impact of the role on productivity when universally deployed to inpatient wards in secondary care.

Methods

This study used a mixed methods approach to explore the roles of WMA in four acute hospitals in the North East and Yorkshire NHS region. The hospitals are operated by a single organisation (known as a Trust) which provides hospital and community care to more than 500,000 people across emergency and urgent care, planned elective surgical and rehabilitative care, maternity and children’s services and end of life care.

Data collection

Two major methods of data collection were used in this study.

Observational data

The perceived impact of the role used data collected by the WMA themselves using a self-administered task-diary (see Appendixes 1,2) and observations. The aim of the task-diary was to capture what WMAs did and how long they did it for. The task-diary was developed using published literature (9) and data was validated with 15 hours of observations by one author (Rumney R) to establish construct validity. Observations allowed secondary confirmation of what WMAs recorded they did and how long they did it for. Task-diary data was collected by a convenience sample of six WMAs over 27 non-consecutive days between November 2021 and January 2022.

Survey data

The second method of data collection used a 13-item survey (see Appendixes 1,2). The aim of the survey was to explore awareness and knowledge of WMAs role with nursing and medical staff. The survey was piloted with a convenience sample of three nurses and two medical colleagues to evaluate readability and construct validity. A convenience sample was recruited via email distribution to all nursing and medical staff across four acute hospitals within the organisation, with follow up face-to-face survey completion by one author (Oxley K) using a tablet on the wards to support data collection. The survey platform was Microsoft Forms, which facilitated easy access via desktop and mobile devices connected to the internet. Seven items used Likert scales to evaluate helpfulness, time saved, pressure relieved and awareness relating to the role of WMAs. One item (Question 6) was reverse scored and negatively worded, to assess internal validity and internal consistency reliability. Four items used free-text responses to explore the perceived impact of the WMAs role.

Data analysis

Numerical and textual data from the task-diaries was transposed into Microsoft Excel, where descriptive statistical analysis was completed. Data from the task-diaries was tabulated manually by one author (Rumney R) and quality checked by another author (Rathbone AP). Simple descriptive statistical analysis was completed by one author (Rumney R) and validated by another author (Rathbone AP) in Microsoft Excel, discrepancies were resolved by discussion and consensus with a third author (Baqir W). Tasks were reviewed through discussion until consensus (by Rumney R, Rathbone AP, Campbell D, Baqir W, Barnfather L and Oxley K) to identify if they were currently completed by nurses, by pharmacy technicians, or both. Data from the task-diaries was then used to identify the average time WMAs spent doing a task (t, hours).

Statistical analysis

A direct comparison of hourly costs for nurses or pharmacy technicians (n) and WMAs (c) was applied to identify daily costs for nurses or pharmacy technicians (Dn) and daily costs for WMAs (Dc) by multiplying the hourly cost by time (Dn = n * t or Dc = c * t). Weekly costs for pharmacy technicians or nurses (Wn) and weekly costs for WMAs (Wc) were calculated by multiplying the relevant daily cost by five (Wc = Dc * 5). Yearly costs for pharmacy technicians or nurses (Yn) and yearly costs for WMAs (Yc) were calculated by multiplying the relevant weekly cost by 52 (Yc = Wc * 52). A linear model of extrapolation to project theoretical cost savings or productivity gains (s) was applied to identify hourly (s), daily (Ds), weekly (Ws) and yearly (Ys) projections, by subtracting relevant costs for nurses from costs for WMAs. Projected productivity gains at capacity over 5 years (l), daily (Dl), weekly (Wl) and yearly (Yl) was calculated by multiplying the relevant productivity gain (s, Ds, Ws or Ys) by the number of WMAs needed to cover nineteen wards at the organisation and then by five (e.g., l = s * 19 * 5). The hourly rate for pharmacy technicians and nurses (n) was £13.84 (Agenda for Change, Band 5) and for WMAs (c) was £11.11 (Agenda for Change, Band 3).

Numerical data from the survey was transposed to Microsoft Excel. Participants that did not complete the survey fully were removed (n=3). Data was cleaned by one author (Oxley K) and validated by another author (Rathbone AP). Data from the survey were grouped to perform sub-group analysis across four groups. This included (I) senior doctors defined as Consultant-level; (II) senior nurses defined as Charge Nurse, Sister, or Matron; (III) junior doctors defined as non-Consultant medical staff; and (IV) junior nursing staff defined as Staff Nurses, Nursing Associates and Healthcare Assistants.

Textual data from free-text responses in the survey were transposed to NVivo, Version 1.2 and thematically analysed. This used a standardised process adopted from the literature (12), including Step 1: familiarisation with the data, Step 2: identification of key codes and categories and Step 3: clustering of codes and categories to form themes. Thematic analysis was completed by one author (Rathbone AP) and discussed at project meetings with other authors (Rumney R, Oxley K, Baqir W), this improved the rigour of the analysis by controlling for consistency and managing bias through reflexivity, audit and using a codebook (12).

Ethics

The study conformed to the provision in the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). Ethical approval was obtained from the Newcastle University Faculty of Medical Sciences Research Ethics Committee (No. 23494/2022) and informed consent was taken from all participants.

Results

Quantitative findings

What WMAs did

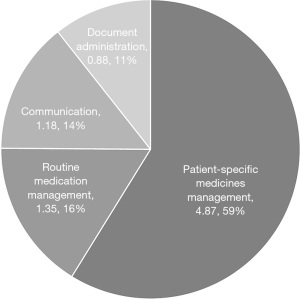

The average total daily hours documented by WMAs in the task-diary across 27 days was 7.12 hours. WMAs spent most of their time, approximately 59% (t=4.87 hours) of each day, on patient-specific medicines management activities (see Figure 1). These included supporting medication use for specific patients such as during the medication administration round, processing discharge medications for patients, checking patient supplies of inpatient medications and dispensing medications. It also included counselling patients about their medications, including medications started on admission but also medications the patient may have been taking prior to admission, and alerting nursing colleagues where medication administration was overdue—this was particularly important for antimicrobial and pain management medications. Helping with ordering or administering Schedule 2 and 3 controlled drugs (3% or 0.23 hours, each respectively) and intravenous medications (7% or 0.61 hours) were also a key part of WMAs daily activities. WMAs also contributed to answering queries, from patients and professionals about specific patients, for 3% (or 0.23 hours) of their time each day on average.

The remaining time in the day was spent on routine medication management activities (16%, t=1.35), relating to medication waste management and maintaining ‘stock’ levels of medications kept on the ward for general use, communications (14%, t=1.18 hours) and document administration (11%, t=0.88 hours). Further details of what each activity included can be seen in Table 2.

Table 2

| Activity | t (hours) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Patient-specific medicines management1 | 4.87 | 59 |

| Medication administration round* | 1.16 | 14 |

| Processing discharge medication*,** | 0.99 | 12 |

| In-patient medication supply check*,** | 0.79 | 10 |

| Dispensing** | 0.23 | 3 |

| Assist with controlled drug ordering*,** | 0.23 | 3 |

| Counselling** | 0.20 | 2 |

| Assist with controlled drug countersignature* | 0.24 | 3 |

| Gathering items for intravenous medication administration* | 0.61 | 7 |

| Preventing missed medication | 0.19 | 2 |

| Answering queries** | 0.23 | 3 |

| Routine medication management2 | 1.35 | 16 |

| Medicine Waste Management* | 0.43 | 5 |

| Omnicell cycle count | 0.16 | 2 |

| Omnicell stock top up*,** | 0.15 | 2 |

| Store drugs/fluids* | 0.24 | 3 |

| Replenish medication cupboard* | 0.17 | 2 |

| Check expiry dates of medication | 0.20 | 2 |

| Communication | 1.18 | 14 |

| Handover** | 0.58 | 7 |

| Multidisciplinary team meeting** | 0.60 | 7 |

| Document administration | 0.88 | 11 |

| Assign sources of electronic medication history** | 0.88 | 11 |

| Total time per day | 8.28 | 100 |

*, activity identified as previously carried out by nursing staff; **, activity identified as previously carried out by pharmacy technician staff. 1, patient-specific medicines management relates to ordering, supplying, supporting administration for specific patients; 2, routine medication management relates to ordering, supplying, managing waste generally for medications held as ‘stock’ on the ward.

Supporting nurses

Of the activities completed by WMAs, approximately ten were identified as supporting nurses (see Table 2), equating to approximately 4 hours and 41 minutes of productivity gains for nurses. Ten activities were identified as being completed by pharmacy technicians equating to 4 hours 52 minutes productivity gains for pharmacy technicians. Investing in this role using an Agenda for Change Band 5 Entry Point Hourly Rate of £13.84 as a nurse salary, and Agenda for Change Band 3 Entry Point Hourly Rate of £11.11 as a WMAs salary for comparison, when each site is at capacity, equated to a projected productivity gain of £325,017.42 over a 5-year period (see Table 3).

Table 3

| Agenda for change entry point* | Nurses and pharmacy technicians cost (£) | WMAs cost (£) | Productivity gains (£) | Productivity gains at capacity over 5 years (£)** |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hour | 13.84 | 11.11 | 2.73 | 259.35 |

| Day† | 66.71 | 53.55 | 13.16 | 1,250.07 |

| Week‡ | 333.54 | 267.75 | 65.79 | 6,250.34 |

| Year | 17,344.29 | 13,923.05 | 3,421.24 | 325,017.42 |

*, figures calculated using Agenda for Change Entry Point 2021/22; **, where capacity means WMAs are working on every ward on site (n=19). †, using the average time WMAs completed activities usually completed by nursing staff; ‡, based on a 5-day working week. GBP, Great British Pounds; WMAs, Ward Medicines Assistants.

Awareness of WMAs

Forty participants completed the survey, made up of medical (n=26) and nursing (n=14) staff colleagues (see Table S1). Approximately 15.0% (n=6) and 17.5% (n=7) had no previous experience or were unsure if they had worked with WMAs in the past, respectively. Results showed a mixed picture regarding awareness of the role of WMAs, with 47.5% of respondents agreeing or strongly agreeing they were fully aware of what WMAs can do at ward level, and 45% agreeing or strongly agreeing they knew what tasks WMAs could do. Senior doctors (Consultant-level) and senior nurses (defined as Charge Nurse, Sister, or Matron) appeared to have the most awareness of the role of WMAs, compared with junior doctors (non-Consultant) and junior nursing staff (defined as Staff Nurses, Nursing Associates and Healthcare Assistants).

Most respondents agreed or strongly agreed that WMAs were helpful (55%, n=22) or provided them with extra time to do other tasks (47.5%, n=19). Most remaining participants (40%, n=16 and 42.5%, n=17, respectively) neither agreed nor disagreed, with the fewest responses indicating members of staff disagreeing or strongly disagreeing that WMAs were helpful (5%, n=2) or provided extra time for them to do other tasks (10%, n=4). Indeed 55% (n=22) of respondents felt WMAs took pressure off nursing colleagues. Similarly, 82.5% (n=33) of participants strongly disagreed or disagreed there was no role for WMAs at ward level, suggesting most respondents felt there was a role for WMAs.

Collectively this data indicates although there may be some ambiguity about the precise or exact role of WMAs, medical and nursing staff do have some awareness of the role and find this to be helpful, providing extra time for other tasks, relieving workplace pressure and cognitive burden.

Qualitative findings

Qualitative thematic analysis of free-text responses identified two themes. Theme 1 improving the quantity and quality of care and Theme 2 integration into the team (see Figure 2).

Theme 1 Improving the quantity and quality of care

Key advantages of working with WMAs identified by participants focused on supporting medication use—including the administration of medications for inpatients, arranging the supply of medications for patients being discharged and improving patient safety.

[the way they are] helping with medications for patients on the ward, I feel they take a lot of time off [the medication administration] rounds for the nurses. [They’re] also extremely helpful getting discharge medication sorted so patients can leave rather than waiting around for the pharmacy delivery.—P30, Junior Nurse.

[They are] very knowledgeable and practical with medications and TTOs [to take out medications]—P13, Junior Doctor.

There was also a clear understanding that the WMAs would help improve productivity by enabling nurses to focus on direct patient care, rather than medication-related tasks.

They allow staff to do other non-medication tasks, so we can focus on direct patient care without worrying about other stuff—P36, Junior Nurse.

This gives the nurses the opportunity to be with patients in a timely manner and more time to interact with patients too, so nurses get to patients quicker so more time with patients but also have a better quality of time with the patients, as they’re not rushing.—P32, Senior Nurse Ward Manager.

Participants recognized an impact the WMAs had on patient safety.

They make discharge [medication supply] safer and easier and this takes the pressure off nurses. They make medication [administration] rounds a lot quicker and safer—P31, Senior Nurse.

They provide support to the whole MDT which helps with safety of medications—P6, Medical Consultant.

This meant WMAs became an integrated part of delivering high quality care.

Brilliant at sorting stuff and heading off other issues that improves the quality of care we give, I could not imagine them not being around and giving patients the same level of care—P25, Medical Consultant.

Collectively, this shows WMAs can improve the quantity and quality of care delivered by other staff by supporting medication-related tasks.

Theme 2 Integrating into the team

Participants reported that there were no disadvantages to WMAs being present on the wards, however some participants did report concerns about how WMAs presence impacted workflow. For example, WMAs absences due to annual leave or sick leave or rotating into different role meant missed opportunities for collaborative working.

I find that [WMAs] aren’t always used properly, sometimes the ward doesn’t know what shifts they are working, if on annual leave. Sometimes they spend more time in the dispensary than on ward—P29, Nursing Associate.

This appeared to be linked to the rotational nature of working patterns and schedules.

[The biggest drawback is they] rotate to different wards. Every ward works differently. The [WMAs] knows how the ward works and the needs of the ward if they are a consistent member of the ward team. Getting a new [Medicines Assistant] every couple of months, does not work—P31, Nursing Sister.

The rotational work patterns and irregular presence of WMAs on the ward reportedly led to contention around access to workstations. This appeared to be confounded by other members of the pharmacy team who were also present on the ward at the same time, which meant on some occasions, ‘pharmacy’ had a large presence which could not be accommodated by the structural layout of the ward and therefore occupied work spaces needed by medical staff.

I know it’s a minor point and all have equal access to work areas, but it can be difficult to do a ward round what the pharmacy team are occupying four workspaces on the ward and covering the notes trolley—P15, Medical Consultant.

Not enough space for them to work due to ward lay out—P22, Medical Consultant.

Collectively, these data suggest that rotational or irregular work patterns may prevent WMAs from becoming embedded within the ward-team, to work within and around the everyday practices of other healthcare professionals.

Discussion

Summary of findings

These findings suggest WMAs have potential to improve the quality of care by completing medication-related tasks in hospital settings, providing productivity gains for nurses and reducing cognitive burden. Finally, although some staff were confident about the role, more work is needed to integrate WMAs as part of the regular, routine ward team and increase awareness about what WMAs can do for medical and nursing staff.

Impact on practice

The findings support existing work that indicated WMAs could improve patient safety, improve productivity and reduce cognitive burden for healthcare professionals (9,10,13). Many organisations are currently reporting high levels of workplace stress, particularly for nurses and consequently struggle to recruit and retain staff (7,14,15). This increases workload for the remaining workforce, creating additional stress and reducing productivity. Therefore, the role of WMAs may provide a novel, alternative and supportive way forward to improve the working lives of nurses—supporting the increasing demand of medication-related task in the delivery of high-quality healthcare (3,16). Importantly, WMAs spent most of their time on patient-specific, medication-related activities, rather than general medication management activities. This reflects existing shifts in the pharmacy profession, which has moved away from product-focused work to patient-focused activities (17). Overall, the findings demonstrated significant potential to impact nursing practice, hospital care delivery and policy.

In this study, some participants did not know what WMAs did or how they could help patients. There is a wealth of literature describing supportive roles, such as pharmacy technicians (18-21), physicians associates (22), and nursing associates (23-26). Comparing these findings to the literature, suggest further work is needed to compare between which of the new support roles (WMAs, pharmacy technicians, physicians associates and nursing associates) could be most suited to complete the task rather than nurses. The qualitative findings demonstrate improved quality of care, which has also been shown for other support staff, particularly nursing associates (23-26). However, the qualitative nature of these findings does not allow for direct comparison between the roles. Further research work is necessary to understand the benefits to focus on outcomes, such as discharge medication accuracy, adherence and quantitative exploration of patient satisfaction to compare outcomes between pharmacy technicians, nursing associates, physicians’ associates and WMAs. The evidence does indicate that WMAs may be able to ‘fill the gap’ in existing paradigms in clinical settings.

Although there appears to be a space for WMAs to be deployed in secondary care settings, this presents additional demands on existing structural and administrative capacity within current estate and facilities resources (i.e., access to computers, spaces to work). Existing research has explored the use of different technology (e.g., mobile computers, desktop computers), in different spaces (e.g., at the bedside, at a nurses station, in a corridor) to support the delivery of care by different healthcare workers (27). As well as the physical facilities needed to enable WMAs to complete medication-related tasks, as most of the tasks completed by WMAs were patient-specific, there may also be increased competition to access patients themselves. Although outside of the scope of this project, there is no published work exploring patients’ perceptions and experiences of care delivered by teams supported by WMAs—further work is therefore needed to find out if WMAs create additional competition for access to patients in inpatient hospital settings. Clearly, there is a conceptual space for WMAs to fill in relation to medication-related task completion, however further work is needed to explore the physical space, estate and facilities required to accommodate an additional member of the healthcare team and what impact this has on other healthcare professionals’ access to patients.

Limitations

The main limitation of the study was population size, especially the small number of nursing participants, which is likely due to the distribution of the survey being via email. No size calculation was completed as the power of the study is expected to be insufficient to establish significance. However, the findings do provide an indication as to the awareness and perception of WMA by medical and nursing colleagues, establishing a base-line level and data collection tool to support future work. A larger sample size, and an equal number of nursing and medical participants, would increase generalisability of the findings. Additionally, as there was poor recruitment of nurses via email, some participants were approached on the ward to complete the survey using a mobile device. The findings must be interpreted with some caution as data from the survey was collected by approaching staff individually on the wards. This can introduce bias in answers (known as the Hawthorne effect) (28), which may particularly impact findings with such a small sample.

Conclusions

In summary, the aim of this study was to explore medical and nursing staff awareness of WMAs and examine perceived impacts on productivity. This study positions WMAs as valuable members of both the nursing and pharmacy ward teams. WMAs carry out a wide range of medicine-related tasks and participate actively in the supply, administration, and management of medications during the in-patient stay and at the point of discharge. Although the findings must be interpreted with caution, they suggest the WMA role provides an opportunity for efficiencies in productivity and improvement in overall safety and quality of care provided by the ward clinical team whilst improving the working lives of nurses. Continuation of recruitment and implementation of WMA at more sites would be beneficial to pharmacy and nursing staff alike. Further work is needed to explore awareness of this new role, the full extent and impact of the role as it matures. A thorough economic analysis, time-and-space study of the access to estates and facilities and patient satisfaction study are also needed to further evaluate this role.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://jhmhp.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jhmhp-23-3/dss

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jhmhp.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jhmhp-23-3/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study conformed to the provision in the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). Ethical approval was obtained from the Newcastle University Faculty of Medical Sciences Research Ethics Committee (No. 23494/2022) and informed consent was taken from all participants.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Roberts A, Charlesworth A. Future demand for health care: a modelling study. Lancet 2012;380:S20. [Crossref]

- Abraham J. Pharmaceuticalization of society in context: theoretical, empirical and health dimensions. Sociology 2010;44:603-22. [Crossref]

- Cooksey JA, Knapp KK, Walton SM, et al. Challenges to the pharmacist profession from escalating pharmaceutical demand. Health Aff (Millwood) 2002;21:182-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hawthorne N, Anderson C. The global pharmacy workforce: a systematic review of the literature. Hum Resour Health 2009;7:48. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- The World Health Organization. Global strategy on human resources for health: Workforce 2030. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241511131, accessed 04/06/2022; 2014.

- International Council of Nurses. The Global Nursing shortage and Nurse Retention. Available online: https://www.icn.ch/sites/default/files/inline-files/ICN%20Policy%20Brief_Nurse%20Shortage%20and%20Retention_0.pdf, accessed 06/06/2022; 2021.

- McVicar A. Workplace stress in nursing: a literature review. J Adv Nurs 2003;44:633-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Buerhaus PI, Donelan K, Ulrich BT, et al. Impact of the nurse shortage on hospital patient care: comparative perspectives. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26:853-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rathbone AP, Jamie K, Blackburn J, et al. Exploring an extended role for pharmacy assistants on inpatient wards in UK hospitals: using mixed methods to develop the role of medicines assistants. Eur J Hosp Pharm 2020;27:78-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Baqir W, Jones K, Horsley W, et al. Reducing unacceptable missed doses: pharmacy assistant-supported medicine administration. Int J Pharm Pract 2015;23:327-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- International Pharmaceutical Federation (FIP). Technicians and pharmacy support workforce cadres working with pharmacists: An introductory global descriptive study. The Hague, The Netherlands: International Pharmaceutical Federation (FIP); 2017.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Thematic analysis: American Psychological Association; 2012.

- Baqir W, Barrett S, Horsley W, et al. Pharmacy assistant supported medicine administration: reducing unacceptable omitted doses. In: Royal Pharmaceutical Society Annual Conference 2012, 9th - 10th September 2012, ICC Birmingham; UK.

- Cummings CL. What factors affect nursing retention in the acute care setting? J Res Nurs 2011;16:489-500. [Crossref]

- Vioulac C, Aubree C, Massy ZA, et al. Empathy and stress in nurses working in haemodialysis: a qualitative study. J Adv Nurs 2016;72:1075-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Haddad LM, Annamaraju P, Toney-Butler TJ. Nursing shortage. StatPearls [Internet]: StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Urick BY, Meggs EV. Towards a Greater Professional Standing: Evolution of Pharmacy Practice and Education, 1920-2020. Pharmacy (Basel) 2019;7:98. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Banks VL, Barras M, Snoswell CL. Economic benefits of pharmacy technicians practicing at advanced scope: A systematic review. Res Social Adm Pharm 2020;16:1344-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Langham JM, Boggs K. The effect of a ward-based pharmacy technician service. Pharm J 2000;264:961-3.

- Koehler T, Brown A. A global picture of pharmacy technician and other pharmacy support workforce cadres. Res Social Adm Pharm 2017;13:271-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Elliott RA, Perera D, Mouchaileh N, et al. Impact of an expanded ward pharmacy technician role on service-delivery and workforce outcomes in a subacute aged care service. J Pharm Pract Res 2014;44:95-104. [Crossref]

- Drennan VM, Halter M, Wheeler C, et al. What is the contribution of physician associates in hospital care in England? A mixed methods, multiple case study. BMJ Open 2019;9:e027012. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lucas G, Brook J, Thomas T, et al. Healthcare professionals' views of a new second-level nursing associate role: A qualitative study exploring early implementation in an acute setting. J Clin Nurs 2021;30:1312-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kessler I, Steils N, Samsi K, et al. Evaluating the introduction of the nursing associate role in health and social care: Interim report. London: NIHR Policy Research Unit in Health and Social Care Workforce, The Policy Institute, King's College London; 2020.

- Taylor M, Flaherty C. Nursing associate apprenticeship – a descriptive case study narrative of impact, innovation and quality improvement. Higher Education, Skills and Work - Based Learning; Bingley 2020;10:751-66.

- King R, Ryan T, Wood E, et al. Motivations, experiences and aspirations of trainee nursing associates in England: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res 2020;20:802. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Andersen P, Lindgaard AM, Prgomet M, et al. Mobile and fixed computer use by doctors and nurses on hospital wards: multi-method study on the relationships between clinician role, clinical task, and device choice. J Med Internet Res 2009;11:e32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wickström G, Bendix T. The "Hawthorne effect"--what did the original Hawthorne studies actually show? Scand J Work Environ Health 2000;26:363-7. [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Rathbone AP, Rumney R, Oxley K, Barnfather L, Fisher D, McFarlane G, Platton C, Smith K, Chandler S, Campbell D, Baqir W. Ward Medicines Assistants: a new role to support nurses with medication-related tasks. J Hosp Manag Health Policy 2023;7:8.