Aiming for health equity: the bullseye of the quadruple aim

Introduction

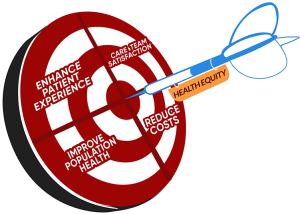

In 2014, Drs. Bodenheimer and Sinsky introduced the Quadruple Aim into our health system improvement lexicon (1). Building off of the Triple Aim articulated by Dr. Berwick (2), an early pioneer of quality improvement in health systems and healthcare, the Quadruple Aim expanded the goals of enhancing patient experience, reducing cost and optimizing population health to include improvements to the work-life and experience of clinicians and care teams that provide care to patients. Immediately after and further catalyzed by emerging literature on the enormous financial, clinical and workforce impact of clinician burnout (3), evolving clinical settings focused on population health and national alternative payment models for advancing primary care delivery in new ways, and the true north for optimal health system performance was codified—it was now reflected in the Quadruple Aim.

In fact, the addition of this 4th aim effectively eclipsed the other aims, because optimization of the initial Triple Aim was now considered impossible without the additional focus on clinician and workforce wellness, resilience and satisfaction. However, what became apparent was that a stringent focus on checking the boxes to the Quadruple Aim was insufficient, in and of itself, to reduce health disparities. The notion that global improvements in quality and delivery of care would improve health disparities and achieve health equity is explicitly false (4).

In fact, the opposite is true. The health system in the United States is one of the most inequitable when compared to peer developed nations. Despite enormous spending on health care per capita, in fact spending more per capita than all other nations in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development combined, the United States has staggering and disappointing outcomes- ranking 28th out of 34 countries in life expectancy, 33rd in infant mortality and 1st in poverty (5,6). In the landmark Mirror, Mirror International Comparison report done by the Commonwealth Fund, the United States ranked last on performance overall, and ranked last or near last on the Access, Administrative Efficiency, Equity, and Health Care Outcomes domains (7). While this performance certainly challenges the health system to rethink its focus, perhaps more confronting is the growing body of evidence about significant health and health care disparities based on race, ethnicity, income, zip code, education and other social determinants (8). For example, in the state of Ohio, known for its alarmingly high rates of infant mortality, numerous initiatives led to an overall decrease in infant mortality from 2009 to 2018, an average decrease of 1.1% per year. However, regardless of these global improvements spurred by advocacy and education initiatives as well as clinical and population health efforts, the Black infant mortality rate has not changed significantly since 2009 and Black infants still die at rates 2.5–3 times higher than White infants (9). Additional complexities are created by the foundational concept of intersectionality (10), so intersectional analyses must be considered in any examination of health disparities in the United States (11). As an example, interlocking systems of oppression for Black women have resulted in Black women in the US having the shortest healthy life expectancy of all racial/ethnic gender groups, even shorter than Black men. Inequities based on race are significantly compounded by gender as well as social inequalities, so any efforts seeking to mitigate disparities based on one system of oppression will likely be unsuccessful (11).

Notable scholar and health equity researcher from the University of California, Los Angeles, Dr. Escarce has stated: “By any measure, the United States has a level of health inequity rarely seen among developed nations. The roots of this inequity are deep and complex, and are a function of differences in income, education, race and segregation, and place (6).”

What then, is equity? The World Health Organization defines equity as the absence of avoidable, unfair, or remediable differences among groups of people, whether those groups are defined socially, economically, demographically or geographically or by other means of stratification (12). Health equity, then, is the goal that everyone gets a fair opportunity to obtain their full health potential and that no one is disadvantaged from achieving this potential (6).

Even with the pursuit of lower cost, population health, patient centered and provider satisfying care, we are at risk of elevating the quality of care for some and exacerbating health disparities for others if we are not actively and intentionally pursuing health equity as its own, unique goal, essentially the bullseye of all of the other aims.

How can a robust health care system apply a health equity centered approach to care delivery? How can we pursue health equity as a moral imperative and not a health imperative (13)? Getting to health equity as the bullseye in the Quadruple Aim requires four important actions: Confronting a painful truth, Shifting focus to accuracy and precision, Applying a health equity lens, and Aligning incentives.

Action 1: confronting a painful truth

To answer these important questions, we must confront a stark but important reality, which is that, the US health care system was never fundamentally designed to achieve health equity. It has never been chartered, whether by legislative pen or breakthrough in diagnostic capability, to achieve health equity. In the midst of a global pandemic such as SARS-CoV2 (COVID-19), this painful truth has been illuminated. For many, the devastation that COVID-19 has rendered on communities of color or lower socioeconomic status has been alarming, but predictable and inevitable (14,15). The legacy of systemic racism, oppressive social injustice and discrimination against Black communities in this nation has disproportionately made Black and other racial/ethnic subgroups incredibly vulnerable to a pandemic of this nature, and vulnerable to future pandemics if we do not reform our structures and institutions significantly. Achieving the Quadruple Aim has been virtually impossible for racial/ethnic minorities and low-income communities, and will remain so until we tackle this truth. Until our healthcare system assigns equal value to the experiences and the pain of a Black expectant mother as it does to the experiences and the pain of a White expectant mother, we cannot move forward. If the root causes of health inequities are not eliminated with upstream, downstream and structural actions, all efforts will be in vain.

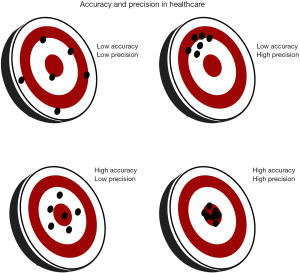

Action 2: pursue both accuracy and precision

Once we have accepted this truth and believe in our moral imperative to obliterate it, we must then focus the pursuit of both accuracy and precision in attaining the health equity bullseye of the Quadruple Aim. In often choosing to be “color-blind” and ignoring the perils that keep us from its true potential, our health care system has scattered its darts, with poorly synchronized and loosely coordinated attempts at repair. This has frequently led to low accuracy and low precision (Figure 1). In some cases, innovations in health care have largely benefited those who are well-resourced to access them, so while they have been extremely precise for certain populations, they have missed the bullseye of health equity with low accuracy. If the populations made most vulnerable by systematic oppression, racism, gender and other discrimination remain at the margins, then even highly accurate programs will miss the mark on precision. Hence, those on the margins must be moved to the center of decision making as we seek improvement. Achieving the bullseye of health equity requires robust intentionality in every aspect of health care education, training, practice, research and engagement, which means that entire curricula, care models and treatment guidelines need to be deconstructed and unlearned, and then built again using a lens or framework for health equity. To have accuracy and precision, each specific aim needs to be re-examined and re-tooled.

In 2007, the World Health Organization produced a document ‘Challenging Inequity Though Health Systems’ as part of their commission on the Social Determinants of Health (SDH). This foundational paper pointed out that Health Systems in and of themselves are social determinants of health. They can, by design, promote health equity: “Health systems promote health equity when their design and management specifically consider the circumstances and needs of socially disadvantaged and marginalized populations, including women, the poor and groups who experience stigma and discrimination, enabling social action by these groups and the civil society organisations supporting them (16).”

The social determinants of health are discussed frequently today in the United States. Much of this has been driven by payment reform, with the ability to use money on programs not rendered at the point of service. Many groups across the country are using screening tools and creating linkages to agencies, or designing interventions themselves. Medical schools are often now teaching about the social determinants of health. Often posed as interventions to promote or attain health equity, they are at risk of being band-aids on much larger wounds. The challenge is that the clinical interventions and teaching methods are still done through traditional lenses (17). Further, the language of ‘Social Determinants of Health’ (SDoH), largely borne out of the global North, may be enhanced by an emerging field of understanding in the global South. Specifically, Central and South America, who have a long history of examining the social processes that can impede healthy living (buen vivir), and more commonly use the phrase ‘Social Determination of Health’ (SDnH) (18). With a focus on determination, there is the additional ability to understand systemic factors that create and reinforce disparities while also examining which, if any, forces may be emancipatory or powerful enough to counter negative impact on health (18). Using a traditional framework in the US healthcare system will still fall short of achieving health equity without a comprehensive framework that couples elements of both approaches. For instance, many electronic medical records have screening tools for food insecurity, a commonly identified social determinant of health. Some medical records systems will generate automatic contact lists for local food banks to be given at the point of the visit. Downstream interventions like these are often well intentioned and can provide benefits such as improved access to healthy food which can potentially improve health outcomes. Often meeting the quadruple aim, they are directed as a population intervention, working to improve patient experience, reducing costs of chronic medical condition care by targeting obesity, diabetes and hypertension, among others. In some cases, addressing SDoH through sharing such resources with a patient improves clinician satisfaction or reduces clinician burnout (19). Such an intervention could be considered potentially accurate, but not precise. Unless intentionally designing interventions with a health equity lens and dismantling the structures that led to the food insecurity in the first place, the health equity bullseye, needing both precision and accuracy, cannot be attained. An example of a more precise and accurate downstream initiative was done by our colleagues at Ohio State University in forming a partnership with a trusted community food collective, and setting up a robust communication system to understand and mitigate risk factors for insecurity, expand services based on usage and also assess patient experiences (20).

Action 3: applying a health equity lens

Once our truths have been confronted and we aggressively pursue both accuracy and precision with our attempts to achieve the bullseye of health equity, it becomes imperative that we look at the examination of processes, clinical care, education and patient experience through a lens of health equity. Multnomah County, Oregon created a Health Equity and Empowerment Lens worksheet and framework that peels away at the layers of work required to uproot inequities upstream, midstream and downstream (21). This construct calls for examination of interventions using a paradigm focused on Purpose, Power, People, Place and Process. It allows users to start asking the hard questions underpinning decision making.

Applying the Quadruple Aim with the goal of achieving that bullseye of health equity, then, looks much different through such lenses. In the previous example of food insecurity, in applying the Health Equity and Empowerment Lens, the Purpose isn’t just improving access to food for individuals in a panel or in a clinical practice, but it is to understand how and why food insecurity is an issue in the first place and how health systems can intervene and advocate. When looking at Power, you see the interventions are often designed from the health system, without input from the communities of whom the intervention is to affect. Understanding that accountability can open systems up to hearing other voices not traditionally ‘at the table.’ What benefits or burdens may have been created by the intervention? When looking more closely at People, analyzing data based on race, gender and zip code would allow more understanding of who in community was affected and allow changes to the intervention to take shape to meet the needs a more defined of population. Looking at Place, issues pertaining to safety or ability to actually use the intervention given transportation or location barriers are considered. Then lastly, Process, how is the intervention empowering individuals and communities? Are there groups intentionally or unintentionally left out? Who are the communities potentially excluded from interventions and services, and why?

Applied consistently, it is this sort of Health Equity lens that can begin to break down exclusionary policies and procedures. To be scaled across the US healthcare system, we must recognize, predict and mitigate barriers. The World Health organization cited four critical health system features that address health inequity, which can be a springboard for the appropriate lens: Leadership, processes and inter-sectoral actions that ultimately promote population health; Aligning organizational arrangements and practices to include populations and those working with marginalized and disadvantaged groups in decisions affecting resource allocation; Reconfiguring health care financing and provision to ensure coverage for all and that resources are distributed towards those who are poorer and have greater health needs; and revitalizing primary health care to reinforce health equity promotion (16).

Action 4: aligning incentives for equity—the power behind the throw

As we strive for the Quadruple Aim, even if the dart is pointed in the right direction to achieve both accuracy and precision, hitting the health equity bullseye requires power to drive it there. That power, or force, is incentive. From a basic economics standpoint, what is the incentive for us to redesign our health care system, training or education, or even just health care policies and procedures, to be more equitable? Is it payment reform? We are skeptical. Our health care system is designed to care for those within its walls. Whether hospital systems, ambulatory clinic systems or private practices, current success is measured on outcomes for those that have accessed these environments for care, and the fees are collected for services completed. Even if we were paid differently, at its core, health equity requires caring about the experience and outcomes of those not within your walls. There is a false assumption that if someone is not accessing one health system for care, they are probably accessing another. This is often untrue and many are marginalized by health care systems that may geographically be down the street from them. We also know that even in caring for people within the walls of a health system, that experience of care can be drastically disparate.

In order to approach equity, the incentive has to come from our society’s agreement to change our societal contract. In Rachel Black and K. Sabeel Rahman seminal report, “Centering the Margins”, they lay out a framework for this change. At its core, they promote centering policies to serve families who have been marginalized by current policy approaches by empowering these families with meaningful voices as programs are designed, and also evaluating interventions based on their experiences (22). There is very little evidence that financial imperatives will ever prevail over an absent moral and internal imperative. We need the moral imperative for that power to back up the throw (13).

A path forward

Our health care system has many of the tools it needs to aim for health equity right now. While for some, the Quadruple Aim continues to be elusive, we believe that focusing our attention towards health equity as the bullseye may be the angle that is needed to truly realize the Quadruple Aim. This may be considered daunting, but the genuine will to achieve health equity could be a powerful motivator to overcome fear, inertia and the paralysis of the status quo. With attention to the four action items in this article, we can start to improve our aim and summon the power needed to get us to the bullseye. At the core, and by far the most important part of this path forward, is an honest stated goal of putting those at the margins, those with the worst health outcomes, at the center of any new policy, practice or procedure. Some would regard this as creating a ‘preferential option for the poor’ while others see this as ‘centering the margins’. In essence, it is both of these things. It requires us asking one critical question: “how is what we are doing going to impact the populations made most vulnerable in our society?” and then acting as if the system will fail should that population not gain the same benefit as the most well served. If we can gather the will to ask and respond to that important question, we will truly be poised to achieve health equity, the bullseye of the Quadruple Aim (Figure 2).

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editors (Naleef Fareed, Ann Scheck McAlearney, and Susan D Moffatt-Bruce) for the series “Innovations and Practices that Influence Patient-Centered Health Care Delivery” published in Journal of Hospital Management and Health Policy. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: Both authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jhmhp-20-101). The series “Innovations and Practices that Influence Patient-Centered Health Care Delivery” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: We confirm that the authors are accountable for all aspects of the work (if applied, including full data access, integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis) and shall ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From Triple to Quadruple Aim: Care of the Patient Requires Care of the Provider. Ann Fam Med 2014;12:573-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The Triple Aim: Care, Health, And Cost. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27:759-69. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Linzer M. Clinician Burnout and the Quality of Care. JAMA Intern Med 2018;178:1331-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mechanic D. Policy Challenges In Addressing Racial Disparities And Improving Population Health. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;24:335-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. OECD Health Statistics 2019 [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jun 9]. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/health/health-data.htm

- Escarce JJ. Health Inequity in the United States: A Primer [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jun 9]. Available online: https://ldi.upenn.edu/sites/default/files/pdf/Penn%20LDI%20Health%20Inequity%20in%20the%20United%20States%20Report_5.pdf

- Schneider EC, Sarnak DO, Squires D, et al. Mirror, Mirror 2017: International Comparison Reflects Flaws and Opportunities for Better U.S. Health Care [Internet]. The Commonwealth fund. [cited 2020 Jun 9]. Available online: https://interactives.commonwealthfund.org/2017/july/mirror-mirror/

- Gottlieb L, Fichtenberg C, Alderwick H, et al. Social Determinants of Health: What’s a Healthcare System to Do? J Healthc Manag 2019;64:243-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ohio Department of Health. The 2018 Ohio Infant Mortality Report. Ohio Infant Mortality [Internet]. Ohio Department of Health. [cited 2020 Jul 9]. Available online: https://odh.ohio.gov/wps/portal/gov/odh/know-our-programs/infant-and-fetal-mortality/reports/2018-ohio-infant-mortality-report

- Crenshaw K. Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics [Internet]. University of Chicago Legal Forum; 1989. (8; vol. 1989). Available online: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol1989/iss1/8

- Richardson LJ, Brown TH. (En)gendering Racial Disparities in Health Trajectories: A Life Course and Intersectional Analysis. SSM - Popul Health 2016;2:425-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Equity [Internet]. Available online: https://www.who.int/healthsystems/topics/equity/en/

- Berwick DM. The Moral Determinants of Health. JAMA 2020;324:225-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yancy CW. COVID-19 and African Americans. JAMA 2020;323:1891-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Laurencin CT, McClinton A. The COVID-19 Pandemic: a Call to Action to Identify and Address Racial and Ethnic Disparities. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 2020;7:398-402. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- WHO. Challenging Inequities through Health Systems. Final Report Knowledge Network on Health Systems. 2007.

- Sharma M, Pinto AD, Kumagai AK. Teaching the Social Determinants of Health: A Path to Equity or a Road to Nowhere? Acad Med 2018;93:25-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Spiegel JM, Breilh J, Yassi A. Why language matters: insights and challenges in applying a social determination of health approach in a North-South collaborative research program. ; [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Olayiwola JN, Willard-Grace R, Dubé K, et al. Higher Perceived Clinic Capacity to Address Patients’ Social Needs Associated with Lower Burnout in Primary Care Providers. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2018;29:415-29. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Clark A, Walker DM, Headings A. Addressing Food Insecurity In Clinical Care: Lessons From The Mid-Ohio Farmacy Experience [Internet]. Health Affairs. [cited 2020 Jun 10]. Available online: https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20191220.448706/full/

- Multnomah County. Multnomah County Equity and Empowerment Lens [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jun 1]. Available online: https://multco.us/diversity-equity/equity-and-empowerment-lens

- Black R, Rahman KS. Centering the Margins A Framework for Equitable and Inclusive Social Policy [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jul 9]. Available online: https://community-wealth.org/sites/clone.community-wealth.org/files/downloads/Centering_the_Margins_r1.pdf

Cite this article as: Olayiwola JN, Rastetter M. Aiming for health equity: the bullseye of the quadruple aim. J Hosp Manag Health Policy 2021;5:11.