Expanding smoke-free communities: attitudes and beliefs surrounding smoke-free casinos and bars in Washoe County, Nevada

Introduction

60% of residents (and 74% of non-smokers) indicated they would favor a law prohibiting tobacco smoking in all casinos in Washoe County, Nevada. Similarly, 63% of residents (and 74% of non-smokers) indicated they would favor a law prohibiting tobacco smoking in all bars. Growing support for smoke-free casinos and bars indicates this should be a priority discussion in protecting the health of Washoe County citizens. Doing so will further reduce the social acceptability of smoking in public places, continue to disentangle the association of smoking and gambling, and help reduce SHS exposure to employees and visiting customers.

In the United States, cigarette smoking remains the leading cause of preventable death. It is responsible for more than 480,000 annual deaths, including more than 41,000 deaths resulting from secondhand smoke (SHS) exposure (1). To curb the tobacco epidemic, governments have introduced policies to create smoke-free environments, which have shown to reduce death and diseases associated with SHS, reduce the number of people who start smoking, motivate smokers to quit, and protect workers from the dangers of SHS (2).

The majority of the literature on smoke-free environments has focused on public indoor spaces, including smoke-free hospitals (3), schools (4), restaurants (5,6), hotels (7), and to some extent on smoke-free bars (5,6,8). Recent efforts have aimed to expand smoke-free communities to further reduce exposure to SHS, including smoke-free outdoor areas (e.g., parks) (9), smoke-free multi-unit housing (10,11), and smoke-free/tobacco-free universities (12). Surprisingly, there has been less attention focused on smoke-free casinos and gaming areas, which might be due to the longstanding relationship between smoking and gambling (13). Amongst the limited smoke-free casino literature, the majority of this research has centered on the economic effects (14-16), and less on the perceived attitudes surrounding these potential policy changes (17,18).

The 2006 Nevada Clean Indoor Air Act (NCIAA) prohibited smoking in all indoor public spaces, except in gaming areas of casinos, tobacco retail stores, tobacco-related trade shows, strip clubs, brothels, and 21-and-over bars (19). Although the NCIAA has led to a substantial reduction in the number of children, workers, and non-smokers exposed to SHS and the health risks associated with SHS, an estimated 182,300 workers in Nevada’s casinos and casino hotels continue to be exposed to SHS in their workplaces (20). Data from the 2016 Nevada Adult Tobacco Survey indicates support for prohibiting smoking in casino gaming areas (52.9%) and bars (44.6%); specifically 49.2% and 42.1% respectively in Washoe County (21). The current study attempts to better understand the gap in coverage related to smoke-free casinos and to explore the current level of support for expanding smoke-free communities by examining more nuanced attitudes and beliefs surrounding smoke-free casinos and bars in Washoe County, Nevada. We present the following article in accordance with the SURGE reporting checklist (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jhmhp-20-78).

Methods

The current study followed a two-stage mixed-methods process. First, two focus groups were conducted to explore residents’ attitudes toward smoking in Washoe County casinos and bars. The results of these discussions helped to identify common themes and trends in public attitudes toward smoking in casinos and bars. Then, the information learned from the focus groups was used to develop a survey to determine whether exposure to information affects residents’ attitudes toward smoking in these establishments.

Focus groups

Participants were recruited from two rotary business group organizations in the Reno-Sparks area using digital flyers distributed through the organizations’ listservs. Participants received a $20 gift card in exchange for their participation. The purpose of the focus group was to better understand how residents felt about the casinos and bars in Washoe County, and specifically how they feel about smoking in these establishments.

A total of 13 participants (54% male) from the Reno-Sparks area participated in the focus group. The focus group sample differed from the Washoe County population on several key demographic factors. Ninety-two percent of participants identified as white (compared to 63.5% for the county population), and the median age for the sample was 58 years old. The participants in the focus groups reported higher than average education levels, with 69% having earned a bachelor’s degree, and 23% having earned a PhD. Among participants who reported their household income, the majority (67%) reported an annual household income of $80,000 or more. The majority of focus group participants were employed in some capacity (69.2%). A minority reported being out of work or retired, and one participant listed “other” for their employment status.

Survey

Participants in Washoe County were recruited through QualtricsTM Panels (online survey software) to participate in this survey. Qualtrics staff emailed panelists the survey link where they could complete the short (5-10 minute) survey online. Participants were paid an average of $3.20 in equivalent market research points. Each panel has its own method of recruitment, but typically respondents can choose to join a panel through a double opt-in process. Upon registration, they enter basic data about themselves, including demographic information, hobbies, and interests. When a survey is created for which that individual would qualify based on the information they have given, they are notified via email and invited to participate in the survey.

The survey questions were developed based upon the information learned in the focus group study. Participants were asked to report on their engagement with casinos and bars in Washoe County in the last 12 months. They were asked about their reasons for visiting these establishments, what they like and do not like about casinos and bars, and then specifically how they felt about smoking and exposure to second-hand smoke. Participants also were asked to answer information about their own smoking behavior and their socio-demographic characteristics including education, income, age, and gender. Later in the survey participants were given a short paragraph to read that included information about the risks associated with exposure to second-hand smoke, based in part upon the evidence focus group participants mentioned they would value, and again asked if they would favor or oppose a law prohibiting tobacco smoking in casinos and bars.

Most of the participants reported their home ZIP CodeTM in the city of Reno (73.03%), while other participants lived in Sparks (20.72%) and outlying communities such as Sun Valley (4.28%), Incline Village, Carson City, Verdi, and Wadsworth (less than 1% each). The sample was 59% female and 39% male and mostly White or Caucasian (76%) followed by Hispanic or Latino (8%), and Asian (7%). This differs from Washoe County overall, which is 49.7% female and 63.5% White/Caucasian and 25.31% Hispanic/Latino (22). The largest age group represented in the sample was the 55 and older group (39.5% of survey participants), while the 18–24-year-old age group represented just 10% of the sample. The age demographics of our sample were comparable to 2018 estimates for Washoe County adult population, of which 38.05% were 55 and older, and 9.36% were between 20 and 24 years old (22).

Most of the participants indicated that they were college graduates (32%) or had completed some college (32%). The most frequently reported pre-tax household income bracket was $40,000 to $79,000 (24%). Participants indicated their political views were mostly moderate (43%), followed by somewhat conservative (22%), somewhat liberal (14%), very conservative (11%), and very liberal (10%). A slight majority of participants (51%) had smoked tobacco or used vaping/e-cigarette products at least once in their lifetime and about one third of the participants (30%) reported current tobacco or vape/e-cigarette usage.

Results

Survey results were previously presented in a technical report (23), and are presented here with additional analyses and context.

Focus group findings

Four themes emerged from the focus groups including, (I) rights of individual businesses, (II) economic concerns, (III) smoking and gambling associations, and (IV) evidence needed to inform decisions.

Rights of individual businesses

Casinos and bars provide a broad range of services including spa services, restaurants, and nightlife. Participants discussed their likes and dislikes about these services in depth. Participants also discussed topics including perceptions of economic impact, health issues and rights, and social participation in relation to smoking. While focus groups appreciated the economic and social opportunities for casinos and bars, they were most bothered by the noise, crowds, and smoky smell (non-smokers and smokers reported this). However, when asked whether casinos and bars in Washoe County should be smoke-free, participants agreed (77%) that the decision to go smoke-free should be a business decision. Six participants (46%) asserted that the government should not make this decision for businesses, for a variety of reasons. Participants in one group discussion in particular expressed concerns about the “slippery slope” of government interference in business decisions.

“I think it should be up to the business to allow it or not to allow it. And not the government telling us, you shouldn’t do this, because again with the slippery slope. Where does it end?”

Economic concerns

Participants in both focus groups shared the belief that casinos were significantly different from other types of businesses due to their size and attraction to tourists, and 77% of participants also believed that prohibiting smoking in these establishments would have a negative impact on the revenue they generate. They also expressed the belief that this would have economic ramifications for the state because they believe that the taxes generated by casinos comprise a large portion of the state’s revenue. None of the focus group participants expressed the belief that a ban on smoking in casinos would have positive economic ramifications for the businesses or the state.

“All these casinos are paying into the state so they’re not going to pull off and say, “it’s all non-smoking or else,” because they’re going to lose a ton of money. It won’t happen.”

Smoking and gambling associations

Throughout the focus group discussions, participants expressed strong beliefs about the culture of gaming, and the perceived association between smoking and gambling. Some participants mentioned previous attempts by Las Vegas casinos to convert to non-smoking facilities in the 1990s only to lift these smoking bans a few years later. Focus group participants seemed to interpret this reversal as evidence of the strength of association between smoking and gambling, and cautioned that banning smoking could have negative economic effects for these businesses. Some believed that international tourism from countries where smoking is still socially accepted would suffer if smoking were banned in casinos here. As one participant explained:

“I wonder if there have been any studies on our foreign visitors. You know we’ve heard from a couple of people that in other countries [smoking is] still quite prevalent. So we’re out there, encouraging people from other countries to come here for economic reasons and so what impact might that have on the foreign visitors as well, economically I think, might be great.”

Some participants also pointed out that both Reno and Las Vegas were largely built upon the gaming industry.

“I think gaming and smoking, they are something that kind of goes hand in hand and I think our entire state has been that way since, I mean the forties, the thirties, I mean you go all the way back to when Vegas and Reno were really in their booming days and early days to even present time.”

While participants supported the business owner’s right to make the final decision to allow or prohibit smoking in their establishment, several discussed the advantages of going smoke-free, such as employee healthcare savings.

Evidence needed to inform decisions

Participants were asked what evidence they would like to see to inform their opinion on establishing smoke-free casinos and bars. Responses included comparisons to other states where businesses have transitioned to smoke-free environments, studies which accounted for contextual factors, and the need for studies conducted locally.

“We’re Nevadans you know… We don’t care what [another state] does, that’s very clear. So what’s happening here locally? I think those studies and that information can then start to influence a lot, influence… everybody ...”

Survey findings

Casino patronage

Nearly all participants in this study indicated they had been to a casino in Washoe County (97%), and of those, the majority had been to a casino within the past three months. The most common reasons cited by participants for visiting Washoe County casinos were dining (76% of participants), gaming (52%), and shows (26%). Participants also indicated the casino activity on which they had spent the most money in the past year. A significant proportion of participants indicated that restaurants were where they spent the most of their money (40%), followed by gaming (32%). Less than 10% of participants reported spending most of their money on each of the other activities (e.g., hotel stays, sports betting, shopping, etc.).

The majority of participants who had visited a casino in the past 12 months (60%) reported that their frequency of visits to casinos had not changed during that time. Among those who reported some change in the frequency of their casino visits, more participants indicated their visits had decreased. Reported patronage trends were similar for bars, with 58% indicating that the frequency of their visits to bars had not changed, and more participants claiming a decrease in their visits, rather than an increase. We asked people whose patronage had decreased to indicate why their behavior had changed. For those who indicated a decrease in bar visits, the most commonly indicated reason was loss of income. For participants who indicated a decrease in casino visits, the most commonly indicated reason was “I don’t want to be in an environment where there is smoking” (which was the third most common reason for bar patrons).

Attitudes toward laws banning smoking/vaping in casinos and bars

Survey participants also responded to four items asking whether they would favor or oppose laws prohibiting smoking in Washoe County casinos and bars. These items were asked separately for casinos and standalone bars, and tobacco smoking (i.e., cigarettes/cigars) was differentiated from all smoking (tobacco plus vaping and e-cigarettes). Overall, 60% of participants indicated that they would favor or strongly favor a law prohibiting tobacco smoking in all casinos in Washoe County, and 57% of participants strongly favor or favor a law that prohibits all forms of smoking (e.g., vaping/e-cigarettes) in casinos. Participants reported similar levels of support for applying these laws to bars (60% and 58%, respectively). Each of these questions was measured on a 5-point Likert type scale, where 5 indicated the highest levels of agreement. Exploratory factor analysis tested whether these four different items captured a single factor. As a scale, this was reliable (α =0.94) and so the average of the four items were used for group comparisons. Overall, non-smokers (m =4.03, sd =1.14) reported greater support for laws banning smoking in casinos and bars when compared to smokers (m =2.52, sd =1.19), t(136) =9.85, P<0.001. There were also differences in support for or opposition to such laws related to household income, F(4,303) =4.61, P=0.001. Participants whose household income exceeded $120k per year (m =4.05) were significantly more likely to endorse these laws than people whose income fell below $20k per year (m =3.09), t(86) =−3.46, P<0.001, as were participants whose income fell between $80–$99k (m =3.93), t(80) =−3.26, P<0.002.

Anticipated behaviors

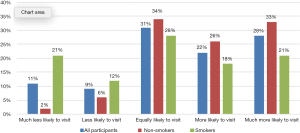

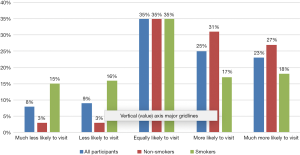

We asked survey participants how they felt their patronage of casinos and bars might be affected if all casinos and bars in Washoe County became completely smoke-free. Response options on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranged from 1= “Much less likely to visit” to 5= “Much more likely to visit.” While the majority of non-smokers claimed that they would either be more likely (26%) or much more likely (33%) to visit casinos if they were smoke-free, responses among smokers were more evenly distributed (Figure 1). A similar pattern emerged regarding bars, with non-smokers responding that they were more likely (31%) or much more likely (27%) to visit bars if they were smoke-free. Again, smokers’ responses were more evenly distributed among the response options (Figure 2).

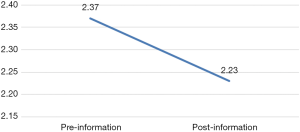

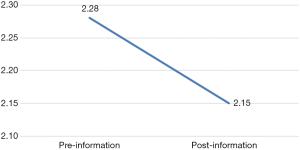

Attitude change following exposure to information about SHS

After sharing their attitudes toward smoking in casinos and bars, survey participants were exposed to narrative information regarding the risks associated with SHS exposure. The narrative also mentioned support for smoke-free policies from the American Cancer Society, the American Heart Association, and the American Lung Association. After reading this information, participants were asked a second time whether they would favor or oppose laws prohibiting tobacco smoke in Washoe County casinos and bars. Results from a repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVAs) demonstrated that the participants attitudes had changed significantly after exposure to this information. Initial opposition to laws prohibiting smoking in casinos was significantly higher (Mdiff =0.137) than opposition after the information exposure, F(1,304) =6.97, P=0.009, np2 =0.022 (Figure 3). Similarly, participants’ attitudes toward laws prohibiting smoking in bars also became more favorable after exposure to SHS information. Before exposure to this information, opposition to laws prohibiting smoking in bars was significantly higher (Mdiff =0.124) than opposition after the information exposure, F(1,304) =4.72, P=0.031, np2 =0.015 (Figure 4).

Right to allow or disallow smoking

Survey participants indicated whose rights were most important in a series of forced choice questions. The majority of participants who responded (78.0%) gave preference to the rights of customers to breathe clean air over the right of smokers to smoke. A slightly smaller majority (66.5%) gave preference to the right of employees to breathe clean air at work over the right of business owners to decide whether to allow smoking (n=305). Finally, a majority of participants (78.2%) thought that the rights of business owners to decide whether to allow smoking was less important than the rights of customers to breathe clean air in casinos and bars (n=239). However, the much lower number of participants responding to this last question should be noted, as it is unknown how the other participants would have responded.

In all three questions, participants suggested that the right to breath clean air was more important. This was different from our focus groups, who by and large suggested that business owners should have the right to make this decision, and who commented that employees and customers bothered by the smoke could choose to frequent other establishments. However, we would caution readers against drawing any conclusions about comparisons that were not measured. For example, we did not ask participants to compare the rights of employees to the rights of smokers.

Discussion

The survey data regarding attitudes and beliefs surrounding smoking and SHS show increasing public support for smoke-free casinos and bars in Washoe County. While the focus group discussions were less supportive of regulation around this issue, most of the participants did agree that the smoke was bothersome, and several participants expressed concerns over the health detriments for employees and customers exposed to SHS in these environments. While previous studies have mostly concentrated on the economic concerns associated with smoke-free casinos and bars, this study aimed to provide a deeper understanding into the limited literature examining beliefs and attitudes surrounding smoke-free policies.

Similar to other studies, the majority of participants who visit casinos and bars prefer they be smoke-free (17), believed there would be an increase in clientele in these establishments if there was a smoke-free policy (14) and either favored or strongly favored a bar and casino smoke/vape free policy (5). Although smokers were less likely to support these policies as shown in other studies (18), research has shown that support for these policies, is much stronger following policy implementation, which provides first-hand evidence of these policy benefits, especially for smokers (24).

Also similar to other studies (6), there is growing support for smoking restrictions within public places in efforts to reduce SHS exposure. In particular, our study reports similar findings that younger generations, specifically millennials, have the greatest support for smoke-free policies due to the harms of SHS (25). Health advocates should present this information to casino and bar owners to illustrate the importance of younger and newer patrons visiting their establishments and in turn secure business support for smoke-free policies.

Despite several studies confirming that there is no safe level of exposure to SHS (26), a majority of participants in both the focus groups and the survey felt that ventilation systems in bars and especially casinos were suitable to prevent SHS. Public health groups should use these findings to educate the public that the only way to fully protect non-smokers from SHS exposure is to prohibit all smoking in indoor spaces and dispel this longstanding myth surrounding ventilation systems and SHS that has been promoted by the tobacco industry (27).

Interestingly, a majority of participants did not mind being around people who were smoking but an overwhelming majority disliked smelling like smoke after visiting a casino or bar. These results highlight some of the individualistic tendencies associated with Nevada voters (28). Following successful approaches in New Orleans (29), media advocacy campaigns should promote smoke-free casinos and bars through a similar individualistic lens (29,30).

Limitations

Although the focus groups were primarily used to construct and develop the survey, the demographics of focus group participants were not representative of the population of Washoe County as a whole. The usage of large panel surveys are supported in similar study designs but there is some skepticism of their usage in the field (for an overview, see Baker) (31). The survey sample in this study was recruited through QualtricsTM, and cannot be considered a probability sample. The survey sample was demographically different from population level estimates with regard to race/ethnicity and gender. In addition to differences between our sample and the general population, it is possible that our sample also differs from populations of casino-patrons (e.g., visitors from California) and casino-employees. Future research on this topic should consider focusing on specific populations that would be directly affected by smoking policies.

Conclusions

Growing support for smoke-free casinos and bars indicates this should be a priority discussion in protecting the health of Washoe County citizens. Doing so will further reduce the social acceptability of smoking in public places, continue to disentangle the association of smoking and gambling, and help reduce SHS exposure to employees and visiting customers.

Acknowledgments

We thank Bronson Frick for providing feedback on this study.

Funding: This work was supported by the University of Nevada, Reno, Renown Health, and the Nevada Tobacco Prevention Coalition (NTPC). The university, Renown and NTPC played no role in the conduct of the research or the preparation of this article.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the SURGE reporting checklist. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jhmhp-20-78

Data Sharing Statement: Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jhmhp-20-78

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jhmhp-20-78). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking-50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, Georgia May 2014.

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Involuntary Exposure to Tobacco Smoke: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, Georgia August 2006.

- McCrabb S, Baker AL, Attia J, et al. Hospital Smoke-Free Policy: Compliance, Enforcement, and Practices. A Staff Survey in Two Large Public Hospitals in Australia. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017;14:1358. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Agaku IT, Obadan EM, Odukoya OO, et al. Tobacco-free schools as a core component of youth tobacco prevention programs: a secondary analysis of data from 43 countries. Eur J Public Health 2015;25:210-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Borland R, Yong HH, Siahpush M, et al. Support for and reported compliance with smoke-free restaurants and bars by smokers in four countries: findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Tob Control 2006;15:iii34-41. [PubMed]

- Azagba S. Effect of smoke-free patio policy of restaurants and bars on exposure to second-hand smoke. Prev Med 2015;76:74-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zakarian JM, Quintana PJE, Winston CH, et al. Hotel smoking policies and their implementation: a survey of California hotel managers. Tob Induc Dis 2017;15:40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tang H, Cowling DW, Lloyd JC, et al. Changes of attitudes and patronage behaviors in response to a smoke-free bar law. Am J Public Health 2003;93:611-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kruger J, Jama A, Kegler M, et al. National and State-Specific Attitudes toward Smoke-Free Parks among U.S. Adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2016;13:864. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ortega KE, Mata H. Our Homes, Our Health: Strategies, Insight, and Resources to Support Smoke-Free Multiunit Housing. Health Promot Pract 2020;21:110S-7S. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Anastasiou E, Feinberg A, Tovar A, et al. Secondhand smoke exposure in public and private high-rise multiunit housing serving low-income residents in New York City prior to federal smoking ban in public housing, 2018. Sci Total Environ 2020;704:135322 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Blake KD, Klein AL, Walpert L, et al. Smoke-free and tobacco-free colleges and universities in the United States. Tob Control 2020;29:289-94. [PubMed]

- Petry NM, Oncken C. Cigarette smoking is associated with increased severity of gambling problems in treatment-seeking gamblers. Addiction 2002;97:745-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tauras JA, Chaloupka FJ, Moor G, et al. Effect of the Smoke-Free Illinois Act on casino admissions and revenue. Tob Control 2018;27:e130-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mandel LL, Alamar BC, Glantz SA. Smoke-free law did not affect revenue from gaming in Delaware. Tob Control 2005;14:10-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Glantz SA, Wilson-Loots R. No association of smoke-free ordinances with profits from bingo and charitable games in Massachusetts. Tob Control 2003;12:411-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tynan MA, Wang TW, Marynak KL, et al. Attitudes Toward Smoke-Free Casino Policies Among US Adults, 2017. Public Health Rep 2019;134:234-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- King BA, Dube SR, Tynan MA. Attitudes toward smoke-free workplaces, restaurants, and bars, casinos, and clubs among u.s. Adults: findings from the 2009-2010 national adult tobacco survey. Nicotine Tob Res 2013;15:1464-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- American Cancer Society. Voter Initiative: Nevada Clean Indoor Air Act. Carson City, Nevada 7 November 2006.

- Nevada Department of Employment Training and Rehabilitation. Research and Analysis Bureau: Sub-State Press Release. Carson City, Nevada 1 December 2019.

- Nevada Institute for Children’s Research & Policy. 2016 Nevada Adult Tobacco Survey. Las Vegas, Nevada 30 June 2016.

- Hardcastle J. Nevada county age, sex, race and Hispanic origin estimates and projections 2000 to 2038: Estimates from 2000 to 2017 and projections from 2018 to 2038. Reno, Nevada: Department of Taxation; May 2018.

- Crosbie E, Wood E, Snider KM, et al. Smoke-Free Community Assessment Report. 14 June 2019.

- Mowery PD, Babb S, Hobart R, et al. The impact of state preemption of local smoking restrictions on public health protections and changes in social norms. J Environ Public Health 2012;2012:632629 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rodriquez EJ, Oh SS, Perez-Stable EJ, et al. Changes in Smoking Intensity Over Time by Birth Cohort and by Latino National Background, 1997-2014. Nicotine Tob Res 2016;18:2225-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- American Cancer Society. Health Risks of Secondhand Smoke: What is secondhand smoke? Available online: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/cancer-causes/tobacco-and-cancer/secondhand-smoke.html 13 November 2015.

- Drope J, Bialous SA, Glantz SA. Tobacco industry efforts to present ventilation as an alternative to smoke-free environments in North America. Tob Control 2004;13:i41-47. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Filippidis FT, Girvalaki C, Mechili EA, et al. Are political views related to smoking and support for tobacco control policies? A survey across 28 European countries. Tob Induc Dis. 2017;15:45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Welch MP. New Orleans goes smoke-free: a breath of fresh air or a blow to its character? 2015. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2015/apr/22/new-orleans-smoke-free-unique-character-smoking-ban. Accessed 23 March 2020.

- Americans for Nonsmokers Rights. U.S. Smokefree Casinos and Gambling Facilities. 2 January 2020.

- Baker R. Research synthesis: AAPOR report on online panels. Pub Quart 2010;74:711-81. [Crossref]

Cite this article as: Crosbie E, Snider KM, McMillen R, Hartman J, Alvarez F, Wood E, Dahir VB. Expanding smoke-free communities: attitudes and beliefs surrounding smoke-free casinos and bars in Washoe County, Nevada. J Hosp Manag Health Policy 2020;4:23.