US trainee perspectives on a national pay-for-performance program

Introduction

Through the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA) and its Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS), Medicare is leading the shift towards value-based payment in the United States (1,2). Effective January 2017, MIPS is the largest US national pay-for-performance program to date and consolidates other nationwide payment programs under four domains: Quality, Resource Use, Advancing Care Information, and Clinical Practice Improvement Activities. Performance in these domains is ultimately weighted and combined to determine upward or downward payment adjustments for most physicians caring for Medicare beneficiaries.

Though MIPS represents a major change for practicing physicians, it is also relevant to resident and fellow trainees who will be directly affected as they enter clinical practice when the policy is in full effect. Moreover, while ongoing debates about the merit and shortcomings of MIPS (3) may lead to modifications in certain policy features, fundamental changes to the focus on the four domains is unlikely. Medicare has remained committed to the policy as generally designed in ongoing rulemaking.

Therefore, given both the phased rollout of MIPS and time trainees spend in graduate medical education, educators have an opportunity to both prepare trainees to succeed under MIPS policy and deliver trainee feedback to policymakers to improve policy design. However, no studies have evaluated trainee perspectives about or knowledge of MIPS. To address these gaps, we conducted the first ever survey evaluating trainee perspectives on MIPS as a national pay-for-performance program among internal medicine residents and fellows.

Methods

In conjunction with the American College of Physicians (ACP) (4), the second largest physician organization in the US, we conducted a web-based survey using a national sample of physicians that contained internal medicine trainees (residents and subspecialty fellows). Our survey included questions evaluating trainees’ perspectives on several focus areas in general as well as MIPS policy in particular.

Trainees were first asked on a five-point scale (Significantly improve to Significantly reduce) how they believed the value of patient care would be impacted by physician efforts in the following focus areas: (I) reporting and performing well on clinical quality measures; (II) initiating or participating in clinical practice improvement activities; (III) controlling patients’ resource utilization; and (IV) implementing and using electronic health records. These areas correspond to MIPS domains but were not identified as such in order to preserve the integrity of the responses independent of perspectives about MIPS.

Other questions evaluated trainees’ willingness to change their clinical decisions and actions in each of the four focus areas in order to improve value, as well as their beliefs about the degree to which performance in these four focus areas are within physicians’ control and should be tied to physician compensation (Not/None at all to A great deal for all questions).

Subsequently, respondents were asked a question about their self-reported familiarity with MACRA and its requirements before being informed that MIPS “financially rewards or penalizes physicians based on participation and performance” in four domains—Quality, Resource Use, Advancing Care Information, and Clinical Practice Improvement Activities—that correspond to the four focus areas. Respondents were then asked on a five-point scale (significantly improve to significantly reduce) how they believe MIPS as a policy would ultimately impact the value of patient care.

In addition, respondents were asked whether new incentives under MIPS would lead to behaviors that could represent unintended consequences. Finally, respondents were asked how they believed Medicare’s merit-based payment system would ultimately affect (Benefit, Harm, Neither, or Not Sure) (I) Medicare patients, (II) Medicare itself, (III) hospitals and clinics that accept Medicare patients, (IV) physicians caring for Medicare patients, and (V) society.

The survey was distributed via e-mail on March 22, 2017 to 393 eligible trainees, with reminders sent to non-responders to encourage survey completion prior to the survey end date of May 7, 2017. Respondents received a $10 gift card for completion of the survey.

Survey responses were summarized using percentages, and medians and interquartile ranges were used to report continuous variables. Chi squared and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to compare categorical and continuous variables, respectively. All statistical tests were two-tailed and significant at alpha=0.05. Analyses were performed using STATA version 14.1 (STATA Corp., College Station, TX). The protocol (#826825) was reviewed and deemed to be exempt by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board.

Results

Of 393 eligible participants, 47% returned complete (n=171) or partial (n=15) surveys. Thirty percent were women and the median age was 30 years (interquartile range 28–32). Respondents and non-respondents did not differ with respect to gender (30% vs. 34%, P=0.50) or age (median age 30 years for both, P=0.30).

Perspectives on the four focus areas

Overall, most trainees reported willingness to change their clinical decisions and actions in the four focus areas for the sake of value (71–84%) (Table 1). In comparison, fewer believed that physicians have at least some control over these four focus areas (54–61%) or that they should affect physicians’ financial compensation (52–61%).

Table 1

| Survey question [n*] | Answer options | |

|---|---|---|

| Not/none at all or a little (%) | Some or a great deal (%) | |

| In order to improve the value of care, how willing are you to make changes to your clinical decisions and actions in each of the following areas? [174] | ||

| Reporting and performance on clinical quality measures | 29 | 71 |

| Clinical practice improvement activities (e.g., care coordination programs, safety checklists) | 16 | 84 |

| Resource utilization by patients (e.g., reducing unnecessary admissions) | 20 | 80 |

| Implementation and use of electronic health records | 18 | 82 |

| In your opinion, how much should each of the following areas affect physicians’ financial compensation? [174] | ||

| Reporting and performance on clinical quality measures | 48 | 52 |

| Clinical practice improvement activities (e.g., care coordination programs, safety checklists) | 39 | 61 |

| Resource utilization by patients (e.g., reducing unnecessary admissions) | 45 | 55 |

| Implementation and use of electronic health records | 40 | 60 |

| In your opinion, how much control do physicians have over each of the following areas? [174] | ||

| Reporting and performance on clinical quality measures | 46 | 54 |

| Clinical practice improvement activities (e.g., care coordination programs, safety checklists) | 39 | 61 |

| Resource utilization by patients (e.g., reducing unnecessary admissions) | 43 | 57 |

| Implementation and use of electronic health records | 40 | 60 |

*, varies due to item non-response.

Most respondents believed that physician efforts in reporting and performing well on clinical quality measures (76%), initiating or participating in clinical practice improvement activities (87%), controlling patients’ resource utilization (84%), and implementing and using electronic health records (80%) would ultimately improve the value of patient care (Table 2). Only a small proportion of respondents believed efforts in these focus areas would reduce the value of care (<10% for each focus area).

Table 2

| Survey question [n*] | Answer options | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Somewhat or significantly improve (%) | Neither improve nor reduce (%) | Somewhat or significantly reduce (%) | |

| How do efforts by physicians to report and perform well on clinical quality measures ultimately impact the value of patient care? [182] | 76 | 15 | 9 |

| How do efforts by physicians to initiate or participate in clinical practice improvement activities (e.g., care coordination programs, safety checklists) impact the value of patient care? [176] | 87 | 10 | 3 |

| How do efforts by physicians to implement and use electronic health records impact the value of patient care? [175] | 80 | 13 | 7 |

| How do efforts by physicians to control patients’ resource utilization (e.g., reducing unnecessary admissions) impact the value of patient care? [175] | 84 | 13 | 3 |

*, varies due to item non-response.

Perspectives on MIPS

Twenty-eight percent of respondents reported being at least somewhat familiar with MACRA and requirements, while 43% reported not being familiar at all. Once informed that the four focus areas corresponded to MIPS domains, a little over half (57%) of respondents believed that MIPS policy would ultimately improve value, while 44% believed it would either have no effect or even reduce value. Belief about whether MIPS would ultimately improve value did not vary by reported degree of policy familiarity (61% among trainees reporting at least some familiarity vs. 55% among those reporting less familiarity, P=0.45). Similarly, respondents’ willingness to change clinical decisions and actions in order to improve the value of care in each of the four MIPS domains did not vary by policy familiarity (P>0.05 for all).

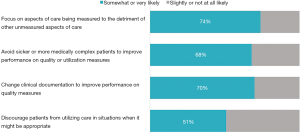

The majority of trainees believed that MIPS would encourage behaviors that could represent unintended consequences (Figure 1). For example, 74% of respondents believed that physicians may be encouraged to “focus on aspects of care being measured to the detriment of other unmeasured aspects of care”. Furthermore, those who endorsed this particular belief were less likely to believe that MIPS would ultimately improve value (51% vs. 73% among who do not endorse this belief, P=0.01). Similarly, compared to those who did not believe MIPS would encourage physicians to “avoid sicker or more medically complex patients to improve performance on quality or utilization measures,” those who endorsed that belief were less likely to believe MIPS would ultimately improve value (49% vs. 73%, P=0.003).

A minority of trainees believed that MIPS would ultimately benefit Medicare patients (19%), Medicare itself (31%), society (18%), or the physicians (13%) and hospitals/clinics (16%) caring for Medicare patients. In contrast, more trainees believed that MIPS would instead harm Medicare patients (30%), society (25%), and the physicians (39%) and hospitals/clinics (38%) caring from Medicare patients. The only group that trainees believed would experience more benefit than harm was Medicare itself (31% believing Medicare would benefit from MIPS vs. 12% believing it would be harmed by MIPS).

Conclusions

In the first survey evaluating US trainees’ perspectives about the largest national pay-for-performance program to date, we provide insight about both the focus areas underlying MIPS as well as the policy itself. Our study has several major findings.

First, like practicing physicians (5), trainees appeared generally positive about the connection between the four focus areas and value. In particular, the majority reported being willing to change their decisions and clinical practice related to the focus areas while also believing that physician efforts in those areas would ultimately improve the value of patient care. It is important to note these positive views from clinicians who will soon enter the workforce and face pay-for-performance incentives.

Second, it is notable that respondents were less positive about the ability of MIPS to improve value compared to physician efforts in corresponding focus areas. While more work is needed to understand this discrepancy among and beyond trainee group (5), it could arise from low policy familiarity or other concerns (e.g., regulatory burden). For example, these beliefs may arise from an underlying notion that with the exception of Medicare itself, other stakeholders may be harmed more than benefitted by MIPS. Regardless, it highlights the opportunity for educators to strengthen education about the connection between general focus areas and policy areas.

Education may be particularly important given that trainees’ self-reported policy awareness was low. While we might expect this result since policy incentives do not directly affect residency and fellowship trainees, it is also consistent with evidence that residents possess knowledge gaps in aspects of value-based care that are highly relevant in clinical practice (e.g., health care spending (6,7), patient satisfaction (8), and incorporation of risk, benefit, and cost information into clinical decisions (9,10) and patient conversations). Educational approaches that emphasize interdisciplinary faculty (11), “train-the-trainer” methods, and supportive environments alongside knowledge transmission (12) may be particularly promising given the need to ensure policy familiarity among practicing clinicians.

Engaging interdisciplinary faculty, including those with expertise in ethics, health equity and policy analysis, would be especially relevant given that most trainees believed MIPS would encourage a set of behaviors that could represent unintended consequences. The fact that beliefs about the impact of MIPS on value varied by beliefs about some of these potentially unintended consequences raise the possibility that addressing the latter through educational initiatives may improve beliefs about the former. Formalizing and delivering feedback gathered from trainees would also help policymakers recognize how to mitigate unintended effects from MIPS policy.

Stakeholder engagement is an explicit focus for Medicare in designing MIPS policy (2), but thus far trainees have not been systematically provided feedback and perspectives about the policy. Given how salient MIPS will soon become for current trainees, educational leaders and policymakers could consider building upon educational initiatives and working together formalize trainee feedback as part of Medicare efforts to optimize policy design.

Finally, our study suggests that trainees are receptive to the notion that controlling costs and patients’ resource utilization can improve the value of care. In the context of payment reform, this represents a departure from traditionally negative resident perspectives on reforms that emphasize cost containment, such as managed care (13), and may instead reflect a contemporary desire for more cost information and a belief that cost containment is part of the social responsibility of every physician (7). Our findings, and the implications of MIPS for trainees upon entering clinical practice, contribute to the momentum behind ongoing movements to educate residents and fellows about cost-conscious care.

This study has several limitations. First, the response rate limits the representativeness of our findings. However, we provide what is to the best of our knowledge the first description of medical trainee perspectives on a large national policy that can help guide future work. Second, while we did not include trainees from non-internal medicine specialties, perspectives captured in our survey are nonetheless salient given that internal medicine metrics have traditionally been major focal points of US (and specifically Medicare) value-based policy and will continue to be under MIPS. Third, we assessed physicians’ overall familiarity with MACRA but not familiarity with each policy element. Fourth, while some questions addressed multiple constructs (e.g., “implementation” and “use” of electronic health records), this was designed to reflect MIPS terminology and the breadth of the policy. Given that we surveyed trainees prior to their being subject to financial incentives under MIPS, future work should monitor perspectives over time as trainees graduate and enter clinical practice. Fifth, we describe the trainee perspectives on a US payment policy. However, our study may provide general insights about how educators can assess trainee perspectives in other contexts given the existence of other national pay-for-performance policies (e.g., in the United Kingdom, France, and a number of others) (14).

Nonetheless, our study demonstrates that US trainee perspectives about a national pay-for-performance program and its underlying focus areas were generally positive, and that graduate medical education and policy leaders can pursue several efforts to prepare trainees and optimize policy design.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jhmhp.2019.08.05). Dr. Liao reported textbook royalties from Wolters Kluwer and personal fees from Kaiser Permanente Washington Research Institute, none of which are related to this manuscript. Dr. Navathe reported receiving grants from Hawaii Medical Service Association, Anthem Public Policy Institute, Cigna, and Oscar Health; personal fees from Navvis and Company, Navigant Inc., Lynx Medical, Indegene Inc., Sutherland Global Services, and Agathos, Inc.; personal fees and equity from NavaHealth; speaking fees from the Cleveland Clinic and personal fees from the National University Health System of Singapore; serving as a board member of Integrated Services Inc. without compensation, and an honorarium from Elsevier Press, none of which are related to this manuscript. Drs. Shea and Weissman have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The protocol (#826825) was reviewed and deemed to be exempt by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). Informed consent was waived due to the nature of the study.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- MACRA. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [accessed 24 May 2019]. Available online: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs.html

- Quality Payment Program. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [accessed 24 May 2019]. Available online: https://qpp.cms.gov/

- Bloniarz K, Winter A, Glass D. Assessing payment adequacy and updating payments: Physician and other health professional services; and Moving beyond the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS). MEDPAC. [accessed 24 May 2019]. Available online: http://medpac.gov/docs/default-source/default-document-library/jan-2018-phys-mips-public.pdf

- American College of Physicians. [accessed 24 May 2019]. Available online: https://www.acponline.org/

- Liao JM, Shea JA, Weissman A, et al. Physician Perspectives In Year 1 Of MACRA And Its Merit-Based Payment System: A National Survey. Health Aff (Millwood) 2018;37:1079-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tek Sehgal R, Gorman P. Internal medicine physicians' knowledge of health care charges. J Grad Med Educ 2011;3:182-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Long T, Silvestri MT, Dashevsky M, et al. Exit Survey of Senior Residents: Cost Conscious but Uninformed. J Grad Med Educ 2016;8:248-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stewart DE, Dang BN, Trautner B, et al. Assessing residents' knowledge of patient satisfaction: a cross-sectional study at a large academic medical centre. BMJ Open 2017;7:e017100 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ryskina KL, Smith CD, Weissman A, et al. U.S. Internal Medicine Residents' Knowledge and Practice of High-Value Care: A National Survey. Acad Med 2015;90:1373-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Patel MR, Shah KS, Shallcross ML. A qualitative study of physician perspectives of cost-related communication and patients' financial burden with managing chronic disease. BMC Health Serv Res 2015;15:518. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Patel MS, Davis MM, Lypson ML. Advancing medical education by teaching health policy. N Engl J Med 2011;364:695-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stammen LA, Stalmeijer RE, Paternotte E, et al. Training Physicians to Provide High-Value, Cost-Conscious Care: A Systematic Review. JAMA 2015;314:2384-400. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Simon SR, Pan RJ, Sullivan AM, et al. Views of managed care--a survey of students, residents, faculty, and deans at medical schools in the United States. N Engl J Med 1999;340:928-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Paying for Performance in Health Care: Implications for health system performance and accountability. The European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. [accessed 24 May 2019]. Available online: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/271073/Paying-for-Performance-in-Health-Care.pdf

Cite this article as: Liao JM, Shea JA, Weissman A, Navathe AS. US trainee perspectives on a national pay-for-performance program. J Hosp Manag Health Policy 2019;3:26.